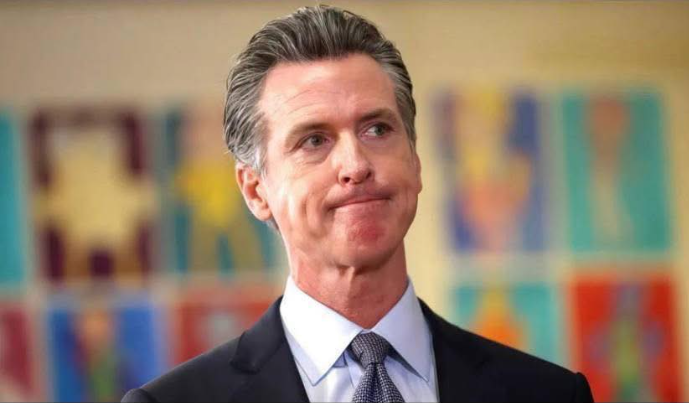

A federal judge has just detonated what was perhaps California’s most ambitious attempt to regulate AI in politics, and the reverberations could reshape every election in the years to come. Laws that Governor Gavin Newsom once hailed as a shield against the chaos of deepfakes have now been struck down as unconstitutional, leaving politicians, voters, and tech platforms alike scrambling to understand what is—and isn’t—allowed. Free speech advocates are cheering, claiming a victory for individual expression, while election watchdogs are sounding alarms over a future where manipulation can occur at the speed of a click. As the 2026 midterms loom, Californians—and indeed, voters nationwide—are left staring into a murky, uncharted political landscape where the lines between fact and fiction may blur more than ever.

The timing of the ruling is almost cinematic. California is gearing up for its first full-scale generative AI election, a political battleground where anyone with a laptop and some coding know-how can fabricate a scandal, stage a confession, or invent an entire conspiracy theory in a matter of minutes. Political campaigns, advocacy groups, and online agitators have already been experimenting with AI-generated content, testing the limits of persuasion, misinformation, and virality. Judge John Mendez, while acknowledging the dangers posed by such tools, drew a hard constitutional line: the state cannot pre-censor political speech, even if that speech is entirely synthetic, weaponized, or designed to manipulate. In his view, the “cure” California lawmakers proposed—preemptive bans and forced content takedowns—posed a far greater threat to the democratic process than the digital lies they sought to control.

By invalidating both the ban on deepfake political ads and the takedown mandate for platforms, the court effectively left Californians navigating almost a completely unregulated information environment. Platforms are still bound by general Section 230 protections, and basic disclosure rules remain in place, but the vast majority of AI-generated political content can flow freely, unchecked. Supporters of the decision argue that empowering the government to decide what is “true” in politics opens a dangerous door to abuse and censorship. They warn that allowing authorities to police speech based on content could easily become a tool for political retaliation, bias, or selective enforcement.

Critics, however, are raising alarms about the consequences of this hands-off approach. They fear that without targeted safeguards, the 2026 election could be flooded with AI-driven misinformation faster than fact-checkers, journalists, or even voters themselves can respond. Imagine a single fabricated video depicting a candidate confessing to a crime, a rival’s campaign being “caught” in a scandal, or an AI-generated news clip that spreads virally before anyone can verify it. These aren’t hypothetical scenarios—they are emerging realities as generative AI tools grow increasingly sophisticated, cheap, and accessible. The clock is ticking, and the capacity for digital manipulation now outpaces traditional mechanisms of accountability.

Platforms like YouTube, Twitter, and TikTok, which host the vast majority of digital political discourse, are now in an unenviable position. They must balance the court’s mandate against pre-censorship with public pressure to combat misinformation, all while avoiding accusations of bias or overreach. Some platforms are experimenting with labeling AI-generated content or offering verification tools for political statements, but the scale of elections and the speed of content creation may render these measures insufficient. In essence, the tools for deception may now outnumber the tools for correction.

Meanwhile, voters face a new, daunting challenge. The average citizen may soon encounter dozens of manipulated videos, AI-generated social media posts, and hyper-realistic images during the course of a single election cycle. Differentiating fact from fiction will require media literacy skills, healthy skepticism, and perhaps a level of digital discernment that most voters haven’t had to employ before. For many, the line between truth and fiction may blur dangerously, eroding trust in institutions, candidates, and even the election process itself.

The stakes are not confined to California. The ruling sets a precedent that could influence courts and legislatures across the United States. Other states, eyeing similar measures to regulate AI in politics, now face a constitutional roadblock. Federal agencies may also grapple with the implications, trying to weigh free speech protections against the potential for destabilizing misinformation campaigns in national elections. In this sense, California’s legal experiment, though struck down, may end up shaping the conversation—and the rules of engagement—for the entire country.

As Election Day 2026 approaches, this court decision will be tested in real time. Candidates, operatives, and ordinary citizens alike will have to navigate a rapidly evolving battlefield where AI-generated content, viral rumors, and sophisticated disinformation campaigns can influence perceptions and voting behavior. The question isn’t just whether the internet can survive the spread of AI-driven lies—it’s whether democracy itself can adapt to the pace and scale of this new digital reality.

In short, California’s failed attempt to regulate AI in politics has opened a Pandora’s box. The balance between free speech and electoral integrity has shifted, leaving voters, platforms, and policymakers to confront one stark truth: the future of elections will be fought not only in town halls and ballot boxes but also in the vast, unpredictable terrain of a synthetic, digital world. How well society navigates this uncharted territory may determine the health of democracy for decades to come.