The human experience is often framed by a quiet assumption: that all of us perceive the world in the same way. We stand side by side with a friend, gaze at the same sun setting behind a skyline, or observe the same bustling city street, and we assume that the mental map we create of these moments mirrors theirs exactly. Yet, consciousness is rarely so uniform. Our perception of reality is fragmented, layered, and endlessly fascinating. The human brain does not passively record light, sound, or motion. Instead, it actively interprets, shapes, and even invents experiences. Each moment we witness is filtered through a dense mesh of personal history, cultural background, emotional state, and instinctive responses. In other words, what we see is never the raw world—it is the world reconstructed through the lens of our own mind. Optical illusions, particularly the class known as “bi-stable” images, offer one of the clearest illustrations of this process. In these illusions, two separate interpretations coexist in a single frame, and which one your brain prioritizes first reveals as much about your inner cognition as it does about the drawing itself.

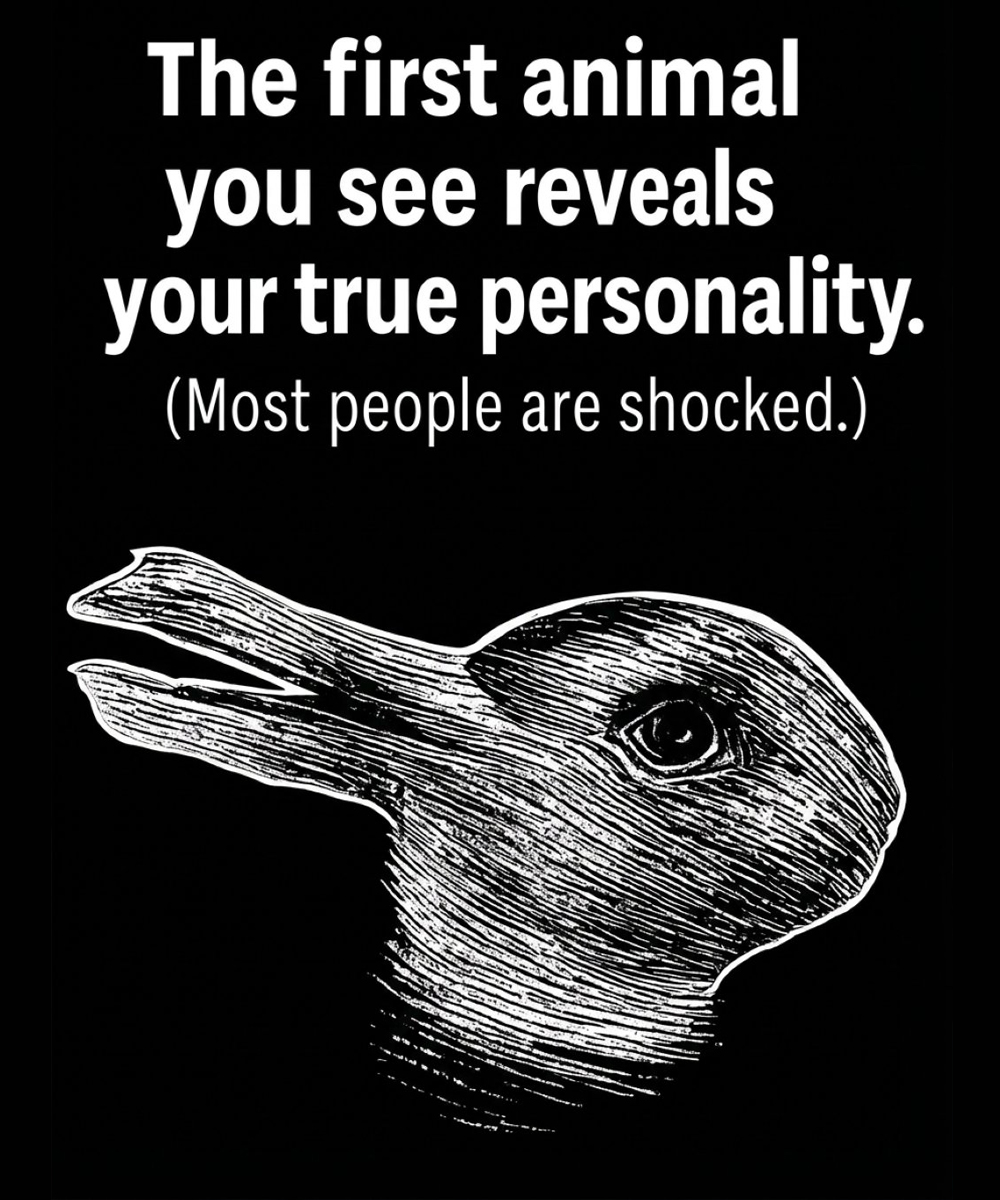

Bi-stable illusions serve as a window into the complex interplay between sensory input and cognitive processing. When confronted with an ambiguous image, the brain undergoes an almost instantaneous negotiation, weighing lines, angles, and contrasts to construct a coherent interpretation. These decisions happen in milliseconds, long before conscious thought enters the equation. They are reflexive, instinctive, and deeply informative about our mental tendencies. The images may appear whimsical—two faces in a vase, a rabbit-duck hybrid—but the underlying mechanism is profoundly revealing. The choices we make in those microseconds reflect our cognitive orientation: are we drawn toward what is concrete or abstract, immediate or conceptual, practical or imaginative?

Take, for example, the legendary duck–rabbit illusion. A deceptively simple set of lines simultaneously represents two entirely distinct animals. The “beak” of the duck also forms the “ears” of the rabbit. Psychologists, neuroscientists, and philosophers have explored this illustration for over a century, intrigued not by its artistry alone but by what it reveals about human perception. For most observers, one animal asserts dominance within the first few moments of viewing. This choice reflects the brain’s default operating mode. It is a split-second signal of how an individual tends to process the world around them.

Those who see the duck first often exhibit a preference for grounded, concrete thinking. The duck represents order, clarity, and immediate recognition. It is practical, observant, and rooted in tangible reality. People whose minds instinctively detect the duck may be methodical problem-solvers, preferring step-by-step strategies to complex ambiguity. They excel in structured environments, thrive under clearly defined parameters, and feel most comfortable when there is a map, a rulebook, or a framework to guide them. In social and professional contexts, they are anchors—reliable, steady, and pragmatic. Their minds are like finely tuned instruments that measure the world in increments, analyzing input logically and systematically. In essence, the “duck” brain values certainty and seeks to impose clarity on a world that is often messy and unpredictable.

In contrast, those who perceive the rabbit first tend toward flexibility, intuition, and imaginative reasoning. Recognizing the rabbit requires the mind to reinterpret the same lines as something entirely new—a subtle mental shift that demands creative agility. The rabbit embodies curiosity, exploration, and emotional perception. Those who spot the rabbit quickly may be natural dreamers, sensitive to nuance, and attuned to subtle cues that others overlook. They often navigate social dynamics with an almost instinctive empathy, reading between the lines and sensing hidden intentions or feelings. Their minds are active laboratories of possibility, exploring “what if” scenarios and symbolic meanings that remain invisible to the more practical, duck-oriented mind. This capacity for imaginative thought fosters originality and innovation, though it can occasionally manifest as overthinking or rumination. Yet the depth of insight and empathy it cultivates is a powerful asset in navigating a complex and interconnected world.

A third, more rare category encompasses individuals whose perception flips effortlessly between the duck and the rabbit or who perceive both simultaneously. This cognitive fluidity signals high mental flexibility and adaptability. People in this group are capable of holding multiple perspectives without succumbing to confusion or cognitive overload. They can negotiate opposing ideas, synthesize contrasting information, and operate effectively in ambiguous or multifaceted situations. These individuals often excel as mediators, problem-solvers, or interdisciplinary thinkers. Their brains resist simplification, embracing complexity and ambiguity as natural components of reality. In a world increasingly polarized by rigid viewpoints, this ability to toggle between perspectives or integrate them is both rare and invaluable.

Beyond the “duck” and “rabbit” typology, optical illusions offer a broader lesson about intelligence and personality. Society often positions logic and creativity as opposing forces, suggesting that the mind must favor one at the expense of the other. Yet the most effective cognition occurs at the intersection of structure and imagination. The “duck” provides the framework, the “rabbit” offers vision. Logic allows us to build a house; imagination transforms it into a home. The first impression—our initial interpretation of a stimulus—is not necessarily definitive. The brain’s rapid choices reveal tendencies, not absolutes, reminding us of the provisional nature of perception itself.

These illusions also cultivate humility. If we can misinterpret a simple set of lines, how often do we misread the intentions, abilities, or beliefs of others? How frequently do we allow our cognitive biases to shape conclusions about people, politics, or society before we have the full picture? Recognizing this inherent limitation encourages curiosity and dialogue. Instead of reacting defensively when someone sees the “beak” while we see “ears,” we might pause and ask, “How do you see it? What am I missing?” This perspective fosters empathy, intellectual openness, and a willingness to engage with complexity.

Another profound insight from optical illusions is the fluidity of personality. We are not permanently “ducks” or “rabbits.” Our minds are dynamic, capable of adapting to circumstances, tasks, and emotional states. A person may exhibit “duck-like” precision and logic while completing tax forms, then reveal “rabbit-like” creativity and emotional insight while composing music or counseling a friend. Personality is not a fixed endpoint; it is a process of ongoing negotiation between instinct, learned behavior, and situational context. Our cognitive orientation is a tool, a lens we can consciously shift to match the demands of the moment.

Ultimately, these illusions teach a deeper truth: perception is choice. We are never entirely prisoners of first impressions, biology, or habitual thought patterns. By training ourselves to see alternative perspectives—by intentionally seeking the rabbit when the duck is obvious—we expand our mental horizons, deepen our empathy, and increase our cognitive flexibility. These exercises remind us that the world is not a static image but a multi-layered, interactive experience. What appears fixed in one instant can be entirely different in the next. The capacity to toggle, reinterpret, and integrate is not merely a quirk of visual perception; it is a profound skill for navigating life’s complexities.

In the final analysis, the duck–rabbit illusion, and its bi-stable cousins, illustrate that human consciousness is as fluid as it is structured. Our minds constantly negotiate between stability and creativity, certainty and ambiguity, logic and imagination. By exploring how we see, how we prioritize, and how we adapt, we uncover the remarkable diversity of thought that exists within us all. In the seemingly simple act of observing a line drawing, we confront a microcosm of human perception: a reminder that the mind is never passive, reality is never singular, and the story we tell ourselves about the world is only one of many possible narratives. To embrace this understanding is to accept both the limitations and the incredible adaptability of human consciousness, ultimately revealing that the richness of experience lies not in fixed perception but in the interplay of perspectives.