I have a strangely clear memory from childhood of noticing a scar on my mother’s arm. It sat high on her upper arm, close to the shoulder, positioned in a way that felt intentional—as if it was meant to exist quietly, visible but not demanding attention.

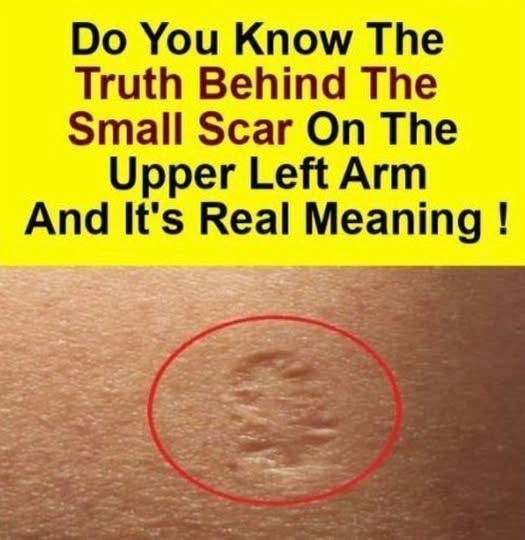

The scar didn’t look like an accident. It wasn’t a scrape or a burn or anything I recognized. It had a peculiar shape: a small circle made up of tiny indentations surrounding a slightly deeper mark in the center. Even as a child, I knew it carried meaning. It looked deliberate, almost ceremonial, like a symbol rather than an injury.

I don’t remember exactly why it fascinated me so much. Children fixate on odd details without understanding why. Maybe it was the symmetry of the pattern, or the way it stood out against otherwise unmarked skin. Whatever the reason, I remember noticing it repeatedly, thinking about it, quietly wondering what kind of event could leave a mark like that.

As with most childhood curiosities, the question eventually faded. The scar never disappeared, but my attention drifted elsewhere. School, friendships, growing up—life rewrote my focus. If I ever asked my mother about it back then, I don’t remember the answer. If she explained it, the explanation didn’t survive the mental clutter of time.

Years passed. The scar became just another unnoticed detail in the background of familiarity.

Then, one summer many years later, something jolted that memory back to life.

I was helping an elderly woman off a train, offering my arm as she stepped carefully down onto the platform. As she adjusted her grip, her sleeve shifted slightly, exposing her upper arm.

There it was.

The same scar. Same location. Same circular pattern. Same unmistakable shape.

For a split second, it felt unreal, like seeing a childhood dream suddenly appear in daylight. The image stopped me cold. This wasn’t coincidence. This wasn’t unique to my mother. This was something shared—something intentional, something rooted in history.

I wanted to ask the woman about it right then, but the moment slipped away. The train doors closed, people moved, and the rhythm of the day reclaimed itself.

Instead, I called my mother.

When I described what I’d seen, she laughed softly. Yes, she said, she had explained that scar to me before. More than once, apparently. My younger brain had simply decided the information wasn’t worth holding onto.

The scar, she told me, came from the smallpox vaccine.

That answer opened a door to a story far larger than I expected.

Smallpox was once one of the most feared diseases humanity had ever known. Caused by the variola virus, it spread easily and killed mercilessly. Infection usually began with fever, exhaustion, and intense pain, followed by a distinctive rash that spread across the body. That rash turned into fluid-filled blisters, then scabs, often leaving deep, permanent scars behind.

At its peak, smallpox killed roughly three out of every ten people who contracted it. Survivors were often left disfigured for life, their faces and bodies marked by pitted scars. In severe cases, the disease caused blindness. Entire families and communities could be devastated in a matter of weeks.

For centuries, smallpox shaped human history. It altered populations, influenced wars, and traveled across continents. No class, nation, or culture was immune to its reach. Fear of outbreaks lingered constantly, an invisible threat waiting to resurface.

The turning point came with vaccination.

The smallpox vaccine was unlike most vaccines we know today. It didn’t use a weakened or inactive form of the smallpox virus itself. Instead, it relied on a related virus called vaccinia, which trained the immune system to recognize and fight smallpox without causing the disease.

Through massive, coordinated global vaccination campaigns, smallpox was steadily driven back. In the United States, it was eliminated by 1952. Routine vaccinations continued for several decades after that, but by 1972, they were no longer given to the general public.

In 1980, the World Health Organization officially declared smallpox eradicated worldwide—the first and only human disease to be completely eliminated.

For people born before the early 1970s, however, the vaccine was a normal part of childhood. And it almost always left a permanent mark.

In a way, the scar functioned like an early form of a vaccine passport: silent proof that the body had been protected against one of the deadliest threats humanity had ever faced.

So why did the vaccine leave such a distinctive scar?

The answer lies in how it was administered.

Unlike modern vaccines delivered through a single injection into muscle, the smallpox vaccine was applied directly to the skin using a special two-pronged needle. The needle was dipped into the vaccine solution and then pressed rapidly into the skin multiple times, puncturing the upper layers.

This method delivered the vaccine into the dermis, triggering a localized reaction rather than a quiet absorption. Over the next several days, a raised bump formed at the site. That bump became a blister, then a scab. The process unfolded over weeks, not days.

This wasn’t a side effect in the modern sense. It was the immune system learning, responding, building protection in real time. The visible reaction was expected. It meant the vaccine was doing exactly what it was supposed to do.

When the scab eventually fell away, it left a scar. The size and shape varied slightly from person to person, but the pattern was remarkably consistent: a circular indentation, sometimes ringed by smaller marks from the needle punctures. Over time, the scar faded, but it never fully disappeared.

Today, that scar is a relic.

It’s a physical reminder of a battle humanity actually won.

In an age when many once-deadly diseases are no longer part of daily life, it’s easy to forget how fragile survival used to be. Medical breakthroughs have made certain fears feel abstract, distant, almost theoretical.

But the smallpox scar tells a different story. It speaks of fear that was once constant, of resilience built through collective effort, of trust placed in science and public health at a global scale.

Seeing that scar now feels different than it did when I was young. What once seemed mysterious now feels heavy with meaning. It’s not just a mark on the skin. It’s evidence of survival, of cooperation, of progress achieved through persistence rather than luck.

That moment on the train reminded me how easily we forget the struggles that shaped the present. Diseases that once defined lifetimes have become footnotes. But for those who lived through them—or through the effort to eradicate them—the memory remains, sometimes literally etched into their bodies.

My mother’s scar is small and easy to miss unless you know what to look for. But now, when I see it, I don’t just see an old mark. I see history.

I see proof of what coordinated public health can accomplish. I see a reminder that the safety we take for granted was earned through decades of research, sacrifice, and collective resolve.

And every time I notice that familiar circular pattern on someone else’s arm, I’m reminded that history doesn’t just live in books or museums. Sometimes, it travels with us quietly, permanently, and meaningfully—carried in skin, memory, and shared human experience.