Most people crack an egg without giving it a second thought. It’s such a routine part of cooking that we rarely pause to consider what’s really going on. Yet beneath that fragile shell is a remarkable natural design, honed over millions of years, built to protect its contents. An egg isn’t defenseless—it comes with its own built-in shield, one that we often unintentionally compromise through modern habits.

Fresh eggs are coated with an almost invisible layer called the cuticle, or bloom. This fine covering seals the thousands of tiny pores that dot the eggshell. Those pores exist to allow air to pass through, giving a developing chick the oxygen it needs. But they’re also potential gateways for bacteria like salmonella. The cuticle’s job is to keep those doors closed, retaining moisture inside and keeping harmful microbes out.

When an egg is freshly laid, this layer is intact and effective. It slows dehydration, maintains quality, and protects against pathogens. As long as the shell stays unbroken and relatively clean, the egg is well-guarded. That’s why, in many countries, eggs are sold unrefrigerated and unwashed—they rely on nature’s protection rather than human processing for safety.

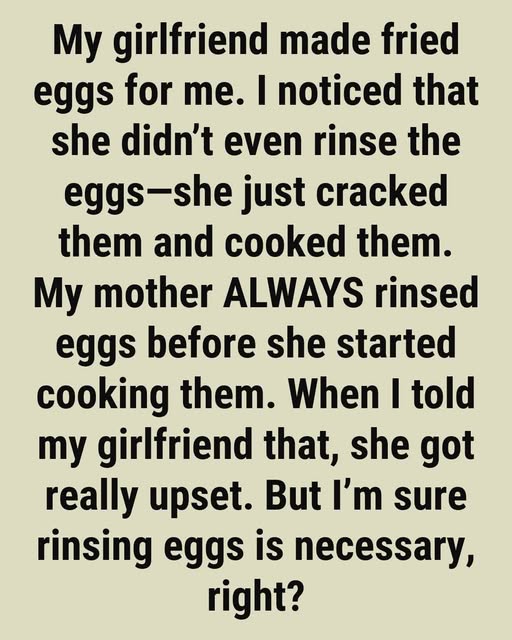

The moment water is introduced, the situation changes. Washing an egg feels like common sense: water cleans, clean equals safe. But in reality, it removes the cuticle almost instantly. Once that barrier is gone, the pores are exposed. Even worse, temperature differences between the egg and water can draw bacteria through the shell, turning a cleaning attempt into a contamination risk.

Industrial egg processing addresses this with strict temperature control, chemical sanitizers, and immediate refrigeration. Once the natural defenses are stripped away, artificial ones must take their place. Without them, washed eggs are more vulnerable, not safer.

At home, this knowledge is crucial. For backyard flocks, farmers’ markets, and organic eggs, leaving them unwashed preserves the cuticle. A little dirt or straw on the shell isn’t dangerous by itself—bacteria can’t easily penetrate an intact cuticle. But moisture changes everything.

Cooking remains the most important factor for safety. Heat destroys harmful bacteria whether an egg has been washed or not. Boiling, frying until firm, baking—all of these make eggs safe to eat. Risks mainly appear when eggs are eaten raw or undercooked, like in homemade mayonnaise, raw batter, or protein shakes. In those situations, careful handling and storage matter more than washing.

Misunderstandings arise because people hear warnings about salmonella and assume washing is enough. It’s not. Proper cooking and safe storage are far more important than routine washing.

Different countries treat eggs differently. In the U.S., eggs are washed, sanitized, and refrigerated before sale. This assumes the cuticle is gone and relies on cold storage to slow bacterial growth. In Europe, eggs are often sold unwashed and unrefrigerated, trusting the intact cuticle for protection. Both approaches can work if done consistently. Problems arise when people mix them—for instance, washing eggs at home and leaving them out of the fridge removes the protective layer without adding any compensating safeguard.

Egg quality matters too. Eggs from healthy hens raised in clean conditions are less likely to carry heavy contamination. That’s why pasture-raised or organic eggs from small farms are often left unwashed until just before use. Cracks, dirt, and smell are better indicators of safety than ritual washing.

Nutritionally, eggs are excellent. They provide complete protein, essential amino acids, healthy fats, choline for the brain, and a wide range of vitamins and minerals. Worrying unnecessarily about cleanliness doesn’t increase safety—it only causes confusion and waste.

Modern food culture often replaces understanding with fear. We sanitize everything reflexively, assuming more intervention equals more safety. Eggs remind us that nature already solved many of these problems. The shell is not just a container—it’s a protective system. The cuticle isn’t dirt—it’s design.

That said, washing may be necessary if an egg is heavily soiled with manure or otherwise visibly dirty—but it should happen immediately before use, never in advance for storage. After washing, eggs must be dried thoroughly and cooked fully. Timing and intention matter more than habit.

Refrigeration works the same way. Once washed or commercially processed, eggs must stay cold. Temperature swings cause condensation, which can encourage bacteria to move. Stability equals safety.

More broadly, the egg story reflects a problem in modern nutrition: advice often comes as slogans without context. “Wash everything.” “Avoid bacteria.” Without understanding the science, these messages can be counterproductive.

Eggs don’t need fear—they need respect.

Next time you handle an egg, remember: what looks fragile is actually well-defended. That thin shell contains a microscopic shield crafted by evolution. Stripping it away out of habit doesn’t protect the egg—it leaves it exposed.

In a world obsessed with control, eggs quietly remind us that sometimes the best action is restraint. Leave the shell intact, store wisely, cook properly, and remember: not every problem needs interference. Sometimes the safest thing you can do is nothing at all.