The ocean did not merely take the Titanic; it obliterated the lives aboard in a way that feels both absolute and incomprehensible. Over 1,500 human beings—men, women, children—vanished into the icy darkness of the North Atlantic, swept into an abyssal grave without markers, without ceremony, without closure. The world above continued to turn, but beneath the waves, a slow and indifferent process had begun. No bodies remained to tell the story of that night. There was no underwater cemetery where families could lay wreaths. Instead, scattered shoes, fragments of clothing, and the occasional personal trinket lingered as silent witnesses, floating or resting in soft sediment, echoes of lives that had been abruptly and irrevocably stopped.

What happened in that cold, lightless tomb was not swift nor clean, but methodical in the indifferent logic of physics and biology. The crushing pressure at nearly 12,000 feet transforms the human body in ways that seem almost unimaginable. Air pockets collapse, soft tissues are compressed and shredded, but the bones, though resistant, do not endure forever. They are slowly consumed—not violently, but patiently—by a combination of microbial activity, scavenging animals, and the chemical processes of saltwater. Flesh persists only for a short while, enough for deep-sea creatures like amphipods and other scavengers to feed, leaving behind fragments and echoes of the human forms that once moved and breathed. The clothing, shoes, belts, and personal items, crafted to survive weather and time, endure far longer than the people who wore them. Leather stiffens, fabric frays, metal fasteners corrode slowly—but these remnants, however resilient, are still temporary. They cling to the seabed like stubborn memories, gradually succumbing to decay and dispersal.

Currents play a merciless role. They tug and twist, shifting remnants across the ocean floor. Heavy sediment gently covers some fragments, erasing their immediate visibility, while lighter pieces drift endlessly, carried by unseen streams. Over time, bones that may have remained start to weaken at a molecular level. Salts, acids, and the slow processes of water chemistry dissolve their structure. Tiny organisms, invisible to the naked eye, gradually consume what remains, turning flesh and even hardened tissue into nourishment for the ecosystem itself. A jawbone, a finger, a rib—once sturdy and full of life—becomes indistinct, integrated into the very fabric of the deep sea, leaving no evidence that these humans ever existed outside the memories of the world above. In this sense, the Titanic’s dead were not buried; they were unmade. Piece by piece, atom by atom, until nothing recognizable remained.

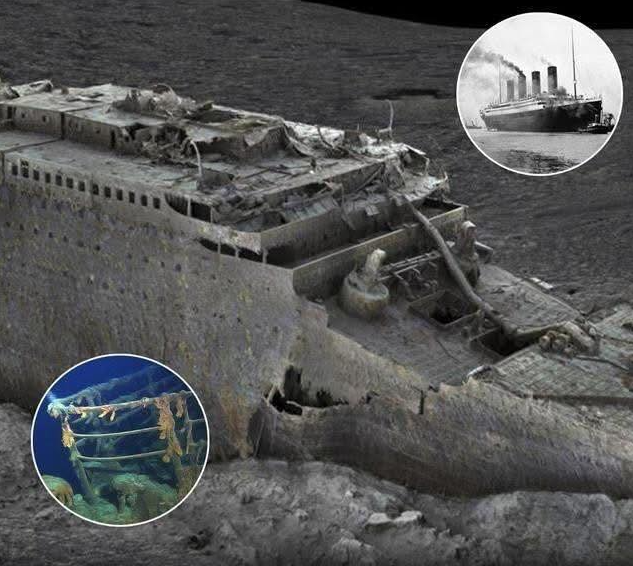

Even as years turned into decades, the ocean’s vastness ensured that the wreck itself was both a tomb and a museum of absence. Steel hulls rusted, decks collapsed, and everything that once formed the grand ship became home to creatures both small and enormous. Amphipods swarmed over clothing fibers. Bacteria colonized anything organic. Rusticles, these iron-eating formations, consumed the metallic remains of the vessel in a slow, almost sentient decay. Shoes, belts, buttons, and fragments of clothing tell the story more poignantly than any body could: these were human lives, interrupted without warning, leaving behind only faint, ghostly echoes. A mother’s shawl, a child’s boot, a sailor’s jacket—they are testimony, not to survival, but to absence. Each piece is a signpost of what once was, a silent record of a life that had dreams, routines, laughter, and fear, all snatched by the indifferent deep.

It is chilling to consider the scale of that erasure. A single wave can drown one person. But at nearly 12,000 feet, the cumulative power of water pressure, cold, and time does more than kill: it removes identity, erases physical presence, and transforms human remains into chemical and ecological components. There is no dignity in death here, no ceremony, no prayers that reach the abyss. Only slow transformation, governed by natural law, carrying away not just the bodies but the tangible proof of their existence. In the absence of bones or preserved flesh, clothing and scattered possessions become haunting symbols: a lone shoe in the sediment, a glove caught in a fold of rusted metal, a fragment of canvas etched by decades underwater. Each speaks louder than words about the lives lost, the suddenness of disaster, and the uncompromising indifference of the deep ocean.

The disappearance is more than physical; it is existential. Families above wept, wrote letters, and preserved photographs, but the sea allowed no correspondence with the remains. The water, silent and infinite, swallowed all that was mortal, leaving grief to wrestle with emptiness. Titanic’s passengers were stripped of the usual markers of mortality: coffin, cemetery, epitaph. Their resting place became a dynamic, ever-changing landscape of deep-sea geology, microbial decay, and scavenger activity. For scientists, the wreck is an archive of extreme preservation and relentless destruction. For humanity, it is a reminder of fragility, vulnerability, and the terrifying majesty of the natural world.

And yet, in that void, there is also a strange, solemn beauty. The ocean performs its work without malice, and in doing so, it transforms the tragedy into a lesson about mortality, impermanence, and the astonishing power of natural processes. The dead of the Titanic do not linger as recognizable corpses, but their absence is palpable. It haunts divers, researchers, and readers alike. Shoes and torn fabric become relics of a vanished society—reminders of the loved ones who boarded with hope and ambition, only to vanish into history, leaving us with only echoes and imagination. The ship is gone, the bodies are gone, and yet the story remains, preserved in collective memory, history books, and the fragmented artifacts that drift silently on the ocean floor.