The majority of people crack an egg mindlessly. Tap, split, pour, and toss the shell—it’s muscle memory. However, that seemingly insignificant, everyday activity conceals a remarkably complex biological system that has evolved over millions of years. Eggs developed their own internal defense long before refrigeration, sanitizers, expiration labels, or contemporary food safety regulations. What seems fragile is actually designed to be protected. And the minute an egg enters the house, a lot of common kitchen practices unintentionally undermine that defense.

Eggshells are more than just fragile containers. The barrier is active. The cuticle, also known as the bloom, is a very thin, invisible coating that covers fresh eggs. Thousands of small pores that would normally function as open entrances are sealed off from the shell’s surface by this natural layer. Its purpose is straightforward but crucial: it prevents pollutants, mildew, and bacteria from getting inside the egg while maintaining moisture within.

In the first place, eggs may survive safely outside of a hen’s body because of this biological barrier. Eggs would deteriorate quickly without it. They can stay stable for long periods of time on it, even in settings without contemporary food storage. Because the shell is porous by nature, a developing chick can exchange gases; however, the cuticle controls this exchange and keeps intruders out. It is not a fault, but a precise equilibrium.

This natural safeguard is appreciated in many nations. Unwashed, unrefrigerated, and easily stored at room temperature, eggs are sold. Farmers are aware of the egg’s exceptional resilience as long as the cuticle is unbroken and the shell is intact. This strategy is consistent with historic food systems that relied less on industrial intervention and more on the protections of nature.

But when an egg is washed, everything is different.

The cuticle is nearly immediately removed by water. All that’s left is a shell with numerous exposed pores that are neither sealed nor shielded. The egg is more susceptible than it was before to washing after that barrier is removed. Particularly if the water used is cooler than the egg itself, temperature variations can actually draw germs from the shell’s surface inward through those pores. Rather from lowering danger, what seems clean can subtly raise it.

For this reason, commercially washed eggs need to be kept in the refrigerator all the time. Due to the removal of the egg’s natural defense, refrigeration is required in locations where eggs are washed as part of industrial processing. Cold storage counteracts the loss of cuticle and limits the growth of microorganisms. Washed eggs would go bad far more quickly than unwashed ones if they weren’t refrigerated.

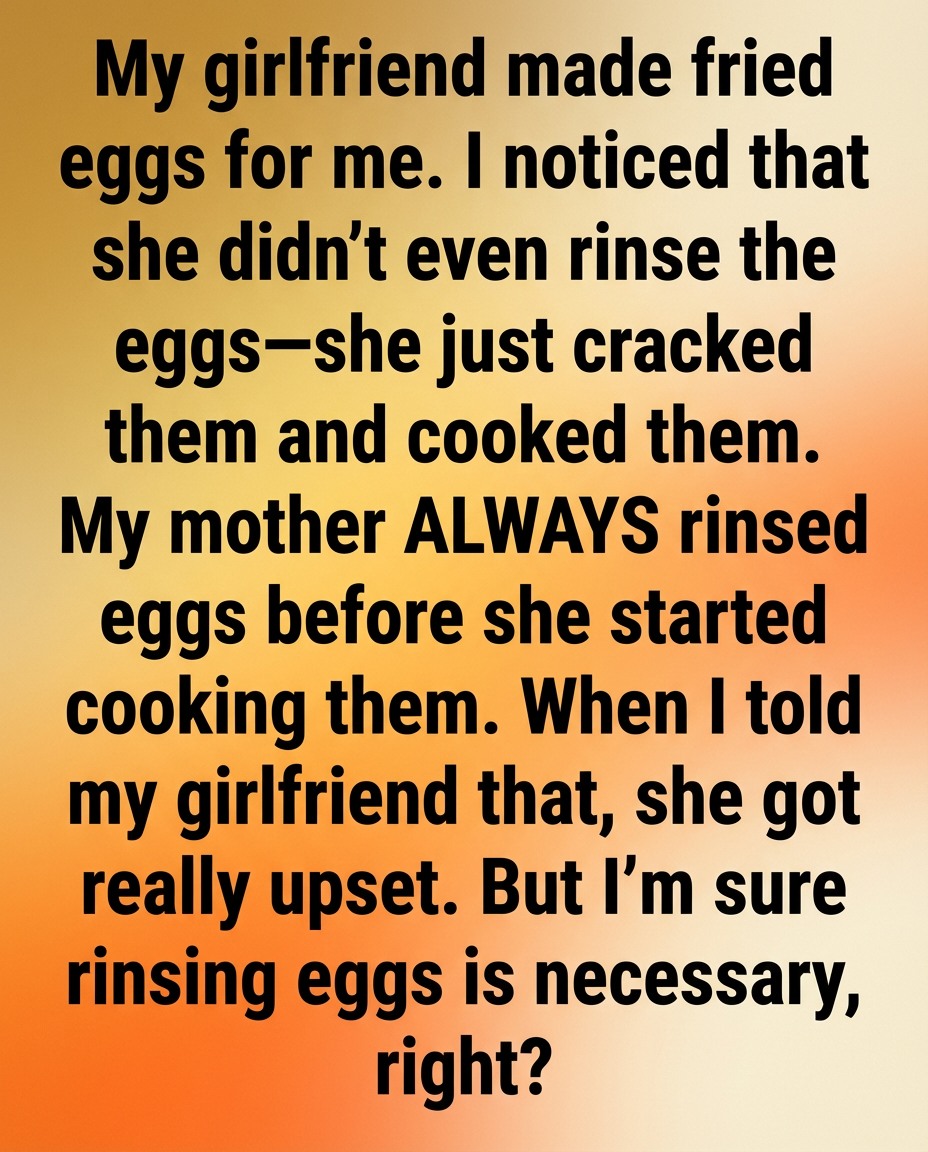

Many people unintentionally duplicate this practice at home. It’s usual practice to wash eggs right away after purchase, before storing them, or “just to be safe.” However, cleaning the egg too soon does more harm than benefit unless it is going to be cracked and fried immediately. It removes protection and produces a surface that needs to be handled carefully and kept cold all the time.

It takes awareness, not fear or obsession, to comprehend this.

The goal of egg safety is not to eradicate all alleged hazards. It’s about appreciating the food’s true function. Hazardous microorganisms are consistently eliminated by proper cooking. Reflexive washing is less important than consistent storage. It is safer to leave an intact, clean shell with its bloom intact than to scour it clean and expose it.

One of the most nutrient-dense foods that people eat is eggs. They offer healthy lipids, choline for brain health, critical amino acids, vitamins B12 and D, and high-quality protein. Because eggs are robust, effective, and naturally protected, they have been a staple diet for ages in societies all across the world. The shell is a component of the system, not waste.

Some eggs may feel a little shiny or powdered, but that isn’t dirt. The bloom is carrying out its function. Removing it too soon is similar to removing paint from metal and then asking why rust develops more quickly. Long before anyone attempted to build upon it, contamination was explained by nature.

Surprisingly easy is the safest course of action. Keep eggs in their original packaging. Keep them chilled if they were chilled at the store. If they weren’t refrigerated when they were sold, don’t wash them until right before using. Washing the shell right before cracking, if necessary, when the egg is ready to cook, presents little risk because the egg will be cooked immediately, removing bacteria anyhow.

In reality, cracks are the enemy. The defense system breaks down if the shell is breached. Instead of washing and storing cracked eggs, they should be thrown out. That’s where being cautious is really important.

This information changes the way we think about handling food on a daily basis. Adding steps isn’t the only way to be clean. Knowing when to stop intervening can be crucial at times. To be safe, eggs don’t need to be sterilized; they just need to be understood.

It’s simple to believe that more intervention equates to more safety in a modern kitchen full of warnings, wipes, and disinfectants. Eggs subtly refute such notion. Their design serves as a reminder that biology frequently found solutions to issues far before technology did.

The next time you hold an egg, you’re holding a self-contained system that has undergone evolutionary refinement. The shell is armor, not delicate packaging. As long as it remains intact, it is invisible, effective, and efficient.

The best food safety practices sometimes involve learning to trust nature rather than altering what it has created.