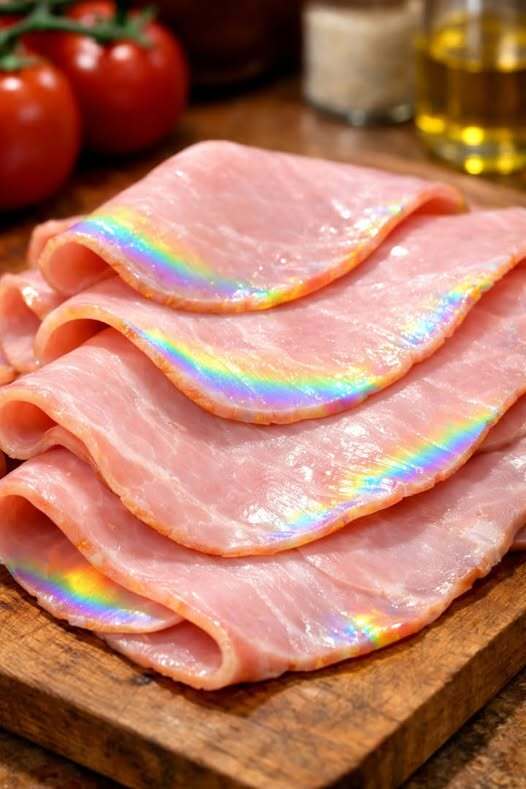

It’s a familiar scene in kitchens everywhere: you peel back the plastic on a fresh pack of ham, and a shimmering, metallic rainbow spreads across the slices. Greens, purples, and blues flash across the pink meat, looking more like a chemical spill than lunch. For many, it’s an immediate deal-breaker—a neon warning to toss the meat. But the science behind this “meat rainbow” is surprisingly harmless, as long as you know how to tell it apart from actual spoilage.

This effect is called iridescence, and it’s purely physical. Ham is made of densely packed muscle fibers. When it’s thinly sliced, especially against the grain, the knife exposes the cross-sections of these fibers. The moist, aligned surface acts like a natural diffraction grating, splitting light into its component colors, much like a CD or a soap bubble. The exact colors you see depend on the spacing of the fibers and the angle of the light. Cured deli ham holds moisture, which enhances the shimmering effect. That unsettling green or blue? Usually a sign of well-sliced, moist ham—not a hazard.

However, iridescence does not guarantee safety. The rainbow can appear alongside actual spoilage, and ignoring other warning signs is dangerous. Deli meats are processed and handled frequently, making them susceptible to bacteria like Listeria monocytogenes. Unlike the harmless light show, spoilage is chemical and biological.

To check if your ham is safe, use all your senses:

Texture: Fresh ham is firm and slightly damp. Sticky, slimy, or tacky surfaces are a definite sign of bacterial growth. A “stringy” film on your fingers means it’s no longer safe.

Smell: Fresh ham smells mildly salty or slightly smoky. Off odors—ammonia, vinegar, sulfur, sourness—indicate bacterial activity, even if the meat looks normal.

Color: True spoilage causes permanent dulling, unlike the shifting colors of iridescence. Gray, brown, or fuzzy white/green patches signal oxidation or mold.

Time: Once opened, deli meats should be eaten within 3–5 days, even refrigerated. Some bacteria, including Listeria, can grow at fridge temperatures without changing smell or appearance.

Storage tips: Wrap slices tightly in foil or plastic, place in an airtight container, and store in the coldest part of the fridge (often the meat drawer) to slow bacterial growth.

In short, the next time your ham sparkles with green or purple, it’s likely just physics at play. But don’t let that optical illusion override real signs of spoilage. Slimy texture, bad smells, or meat left in the fridge for too long are red flags. By combining an understanding of iridescence with careful checks of texture, smell, and storage time, you can safely enjoy your sandwich without feeding bacteria.