It was a quiet afternoon in the Johnson household, the kind of lazy Sunday where the sunlight streamed gently through the half-open blinds, painting soft, golden stripes across the worn wooden floor. Little Tommy Johnson, an inquisitive boy of six, wandered around the living room, his small feet padding softly on the rug, his eyes wide with curiosity as always. His mind, a whirlwind of half-understood instructions, stories, and overheard conversations, was a maze that only he could navigate.

Tommy had always been fascinated by electricity. Not in the scientific sense — though he had learned a few basics from his kindergarten lessons and the occasional YouTube clip his mother occasionally allowed him to watch — but in the magical sense. To him, electricity was an invisible force, a mysterious power that could make the lights shine, the television flicker to life, or the toaster pop with a satisfying pop! And yet, like most six-year-olds, he struggled to fully understand the nuances of adult speech.

It had all started the previous evening. Tommy had been helping his father clean up after dinner, dutifully wiping the table while humming a song he had invented on the spot. He had overheard a conversation — or at least part of one — between his parents. His father, in a tone somewhere between exasperation and jest, had said, “Turn off the light and put it in your mouth.” To Tommy, this sounded like a serious, straightforward instruction. The kind of instruction one would follow if one wanted to be a good son. Only, of course, he didn’t yet grasp the nuance or context.

So now, the next day, his little mind wrestled with a profound, pressing question: could one actually eat electricity? The thought had haunted him all morning, twisting and turning as he carefully examined every electrical appliance he passed. The lamp on the side table, the glowing screen of the television, the refrigerator humming steadily in the kitchen — all tantalizing possibilities, all forbidden.

Unable to contain himself any longer, Tommy approached his mother, who was kneeling in the kitchen, arranging a small pile of colorful vegetables on a cutting board for lunch. She looked up from her task as her son toddled over, his face a mixture of earnest curiosity and mild panic, his little eyebrows furrowed in concentration.

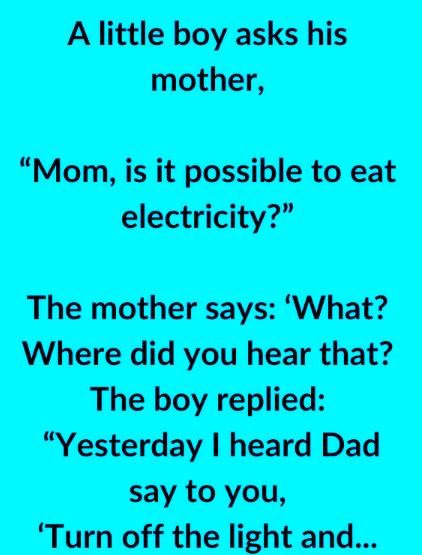

“Mom,” he said, his voice soft but insistent, “is it possible to eat electricity?”

His mother froze mid-chop, the knife hovering in the air as she blinked at him, trying to parse the question. Her mind raced — had he been watching too many cartoons again? Was this a phase, one of those strange six-year-old inquiries into the nature of the world? She tried to respond calmly, not wanting to alarm him.

“What?” she asked cautiously, setting down the knife. “Where did you hear that?”

Tommy looked up at her, eyes wide and serious, as though expecting a definitive answer, as though the entire fate of the universe might rest on her response. “Yesterday,” he said, “I heard Dad tell you, ‘Turn off the light and put it in your mouth.’”

His mother stifled a laugh, realizing immediately what must have happened. Her husband, teasing or perhaps speaking sarcastically, had not meant for their son to take him literally. But of course, Tommy had taken it literally — as only a child could.

“Oh, sweetheart,” she said, kneeling down so she could be at eye level with him, “electricity isn’t something you can eat. It’s very dangerous. You could get hurt if you try to put it in your mouth. That’s why grown-ups are always so careful with it.”

Tommy’s face scrunched up, a mix of confusion and disappointment, as he tried to reconcile this revelation with the instructions he had overheard. “But Dad said—”

“I know, honey,” she said gently, placing a hand on his shoulder. “But sometimes adults say silly things, or they joke. Not everything grown-ups say is meant to be done literally.”

Tommy nodded slowly, the corners of his mouth twitching as he tried to digest this information. “Okay,” he said at last, “so… no electricity lunch today.”

His mother laughed again, relieved, and gave him a hug. “Exactly, no electricity for lunch. Let’s stick to sandwiches and carrots for now.”

Tommy’s eyes brightened a little, and he scampered off toward the living room, muttering to himself about how strange adults could be, but also plotting his next culinary adventure — perhaps a sandwich shaped like a lightning bolt, to capture the magic of electricity safely.

And so, in the Johnson household, a brief misunderstanding sparked a story that would be retold for years — a humorous reminder of the unique ways children interpret the world, and the surprising seriousness with which they approach even the silliest of statements.