Cyd Charisse held a special place in the heyday of MGM, when the studio system produced gods and goddesses with industrial accuracy. Singing, acting, and navigating the intricate geometry of a musical piece as if the score were a physical force coursing through her veins, she was a lady who seemed to be able to do it all. Her figure, characterized by graceful athleticism and famous, infinite lines, became into a Hollywood icon. However, this movie icon originated in a dusty corner of Texas and was born out of a struggle for basic physical survival rather than amid the glamour of a soundstage.

Tula Ellice Finklea, the lady the world would know as Cyd, was born in Amarillo, Texas, in 1922. Her early years were characterized by frailty rather than grace. In a time before vaccinations, Tula was diagnosed with polio before turning six, which was a scary diagnosis. The illness threatened to cause her limbs to wither and confine her to a physically limited life. Doctors recommended ballet classes as a kind of physical therapy—a way to regain the strength she had lost to the virus—in a move that was both pragmatic and prescient. Nobody in that tiny Texas town could have predicted that these meticulous, corrective actions would eventually shape one of the most captivating personas in movie history. Her brother’s lisping attempt to say “Sis” gave rise to her professional name, “Cyd,” which was a holdover from her early years. It gained the nickname for a metamorphosis from a weak Texas girl into a movie princess.

In the 1920s, Amarillo was a region of wide skies and dirt, where there were few prospects for glitz but the horizon seemed endless. The dance studio provided little Tula with a sense of discipline, a sense of grace, and a literal means of escape that the high plains could not provide. Ballet reshaped her confidence in addition to healing her body. She discovered how to use her physical frailty as a source of powerful control. She outgrew Texas by her teens and relocated to Los Angeles, where she studied under strict Russian instructors. In order to meet the need for exoticism of the time, she frequently performed under Russian-sounding pseudonyms during her early years on stage, but her talent—poised, athletic, and refined—was unquestionably her own. Her cinematic personality, a grounded, earthy sensuality, was skillfully matched to the stiff, classical lines of traditional ballet.

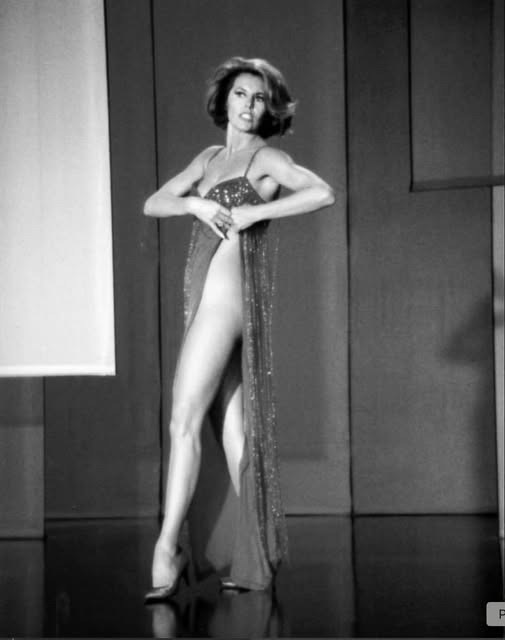

Her movement was so eloquent that Hollywood eventually found her. Charisse’s body language was a language in and of itself, therefore she didn’t need a monologue to grab a director’s attention. She started at the bottom of the call sheet and worked her way up until she signed with MGM in the 1940s. She transitioned from ensemble to feature roles, and by the early 1950s, she was one of the studio’s biggest draws. In the “Broadway Melody” segment of Singin’ in the Rain (1952), she made her debut. She exuded a combination of menace and total control while wearing a slinky green dress that seemed to glitter with life of its own. Even though she didn’t say a single word during the scene, she conveyed everything with a whip of her leg or a tilt of her chin. The contract dancer became an icon in that one performance.

Charisse is unique in that she was a favorite partner of the two titans of movie dancing, Fred Astaire and Gene Kelly. She was the only performer who could blend in with their wildly disparate styles without getting eclipsed. She countered Kelly’s muscular, vivacious athleticism with a cold, piercing accuracy. She looked poetic and lovely with Astaire, personifying rhythm. Their “Dancing in the Dark” scene from 1953’s The Band Wagon is still considered the height of romantic film. There are just two people walking through a park, drawn together by a sort of rhythmic gravity, without any preface or conversation. It was chemistry on display, not just choreography.

Despite the fact that the cameras obviously loved Cyd Charisse, her brilliance was never just about her looks. Her ability to stretch and release a beat in a sophisticated manner was the reason. She had amazing line and control thanks to her ballet training, but she also had the jazz-like sensibility to know when to break the rules. In an instant, she could transform classical shapes into something more contemporary and provocative, going from a quiet stillness to a blaze of movement. She entranced her audience with restraint, making them feel the tension of a half-second hesitation and the breath before a turn, while other dancers tried to amaze with pure speed.

She came to represent elegance during the 1950s. She gave Brigadoon (1954) a radiant, ethereal grace, The Band Wagon sophistication, Singin’ in the Rain mystery, and Silk Stockings (1957) a dry, sardonic wit. Her performance as a nightclub dancer caught in the underworld’s gears in Party Girl (1958) demonstrated her ability to handle darker, more serious material. She proved that she could do a scene with the same seriousness that she used to perform a dance routine.

But off-screen, Charisse didn’t look much like the femme fatales she played. She was a woman of strict professionalism and quiet, constant calm. She maintained a committed sixty-year marriage to singer Tony Martin while remaining a beacon of stability in a profession driven by scandal and excess. With two boys and the motto, “We never tried to outshine each other,” they were a rare Hollywood success story.

Even with the beauty on the outside, her existence was nonetheless characterized by pain. Tragic events occurred in 1979 when her daughter-in-law perished in one of the greatest aviation tragedies ever—the crash of American Airlines Flight 191. She was devastated by the death, according to those who knew her, but she handled it with the same calm fortitude that characterized her dance. She finally returned to teach future generations after stepping aside from the limelight to concentrate on her family. In addition to her skill, dancers were drawn to her because of her self-control and humility.

With appropriate prominence, she received recognition for her achievements. She received the National Medal of Arts from President George W. Bush in 2006. The little girl who had to relearn how to walk via ballet was now being recognized as one of the greatest artists in American history, and it was a moment of deep closure. She left behind a collection of work that is still vibrant when she died in 2008 at the age of 86.

Cyd Charisse taught the world that true grace is the result of intense discipline and deep fortitude, and that beauty doesn’t have to be brittle. Her life was a lesson in how to use physical vulnerability as a source of long-lasting power, not just a Hollywood success story. She not only survived polio, but she overcame it, giving the world a language of movement that continues to be sung over the years. You can still sense the silent miracle of a woman who elevated rehabilitation to a high art form when the lights go down and her image emerges on screen.