A Tragic Summer Day: The Story of Jaysen Carr

It was supposed to be a perfect Fourth of July — a day filled with laughter, splashing water, and the sound of fireworks echoing across Lake Murray. Families gathered along the shore, children ran barefoot on the sand, and parents watched proudly as their little ones dove into the warm, glistening water. For the Carr family, it was one of those rare, carefree summer days — the kind that feel endless, the kind that you think will live forever in your memory.

But for Clarence and Ebony Carr, that memory would soon turn into something unbearable — a memory wrapped in grief, questions, and the silence of a home missing its brightest light.

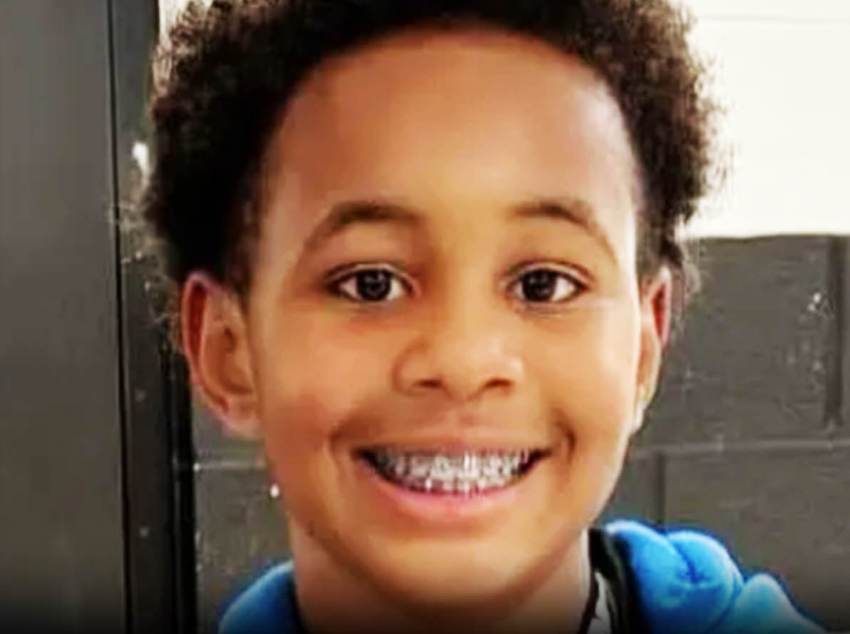

Their 12-year-old son, Jaysen Carr, was full of life — an energetic boy with a smile that could light up a room, a student who excelled in school, a big brother who never failed to make his siblings laugh. He loved tinkering with gadgets, building small machines out of whatever he could find, and talking excitedly about becoming an engineer one day. But above all, Jaysen loved the water. He could spend hours swimming, diving, and racing his friends — fearless, happy, free.

That day at Lake Murray felt no different from the dozens before it. The sun shone high, the water was warm, and laughter filled the air. Nobody could have imagined that something so beautiful could hide something so deadly.

A few days later, Jaysen began to feel unwell. It started with headaches — small at first — then came the fever, the nausea, the confusion. His parents thought it might be a flu, or maybe exhaustion from the summer heat. But the symptoms grew worse with frightening speed. Within days, they rushed him to Prisma Health Children’s Hospital-Midlands, terrified and desperate for answers.

Doctors ran tests. Machines beeped. Nurses moved quickly around the room. And then came the devastating diagnosis — one no parent could ever prepare for. Jaysen had been infected by Naegleria fowleri, a microscopic organism known as the “brain-eating amoeba.” It had entered his body through his nose while swimming in the lake. From there, it had made its way to his brain, causing an infection so rare and so aggressive that almost no one survives it.

The medical team did everything they could. They used every treatment available, every bit of knowledge, every ounce of hope. But the amoeba moved faster than medicine could follow. Within days, Jaysen’s body could no longer fight. He passed away surrounded by his heartbroken parents — Clarence holding his hand, Ebony whispering prayers through tears. The South Carolina Department of Health later confirmed that it was the state’s first case of Naegleria fowleri since 2016.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) explains that this deadly amoeba lives naturally in warm freshwater — lakes, rivers, ponds, and hot springs. It thrives in high temperatures, especially during the summer. In rare cases, it can also be found in poorly maintained swimming pools or splash pads. Between 1962 and 2024, only 167 infections had been reported in the U.S. Out of all those cases, only four people survived. The odds are almost unimaginable — and yet, for one South Carolina family, those odds became a cruel reality.

Days after Jaysen’s passing, his parents stood before cameras at a press conference. Their faces carried the weight of unimaginable loss. Clarence tried to speak, his voice shaking, his hands clenched tightly together as if holding on to the last piece of strength he had.

“This is a very tough situation,” he said softly. “We’re doing the best that we can, but please understand — we don’t want this to happen to anyone else. We’re here to raise public awareness and go from there.”

Beside him, Ebony stood wearing her son’s all-state champion headband — the same one he had worn with pride after his last game. It was one of the few tangible things she had left of him. Her eyes glistened with tears that refused to fall as she spoke.

“If we had known the risks of swimming in that lake,” she said, her voice trembling, “we never would’ve gone near it. We want other parents to know — warm freshwater can be dangerous. People need to know the truth, so no one else has to feel this pain. We don’t want his death to be in vain.”

Since that day, health officials have been reminding the public of vital safety measures: avoid diving or jumping into warm freshwater during the summer, keep your head above water when possible, and use nose clips or hold your nose shut if you go under. These are small steps — but they can save lives. Because when Naegleria fowleri strikes, it gives little warning and no mercy.

The early symptoms often mimic common illnesses: fever, nausea, headache. But within days, the infection progresses rapidly — confusion, hallucinations, seizures, coma. By the time it’s diagnosed, it’s almost always too late.

For Clarence and Ebony, there is no such thing as moving on. The house feels quieter now. Jaysen’s laughter — once constant — echoes only in memory. His room remains untouched, a time capsule of who he was: half-built robot parts on his desk, medals hanging from his bedpost, a notebook filled with sketches of inventions he never got to finish.

Friends, neighbors, and strangers from across the country have reached out. A GoFundMe campaign created in his memory has raised more than $58,000, with messages of love and sorrow pouring in.

“Jaysen was an incredible son, a devoted brother, and a true friend,” one post read. “He faced this battle with courage beyond his years. Though his life was short, his light will shine forever.”

Local teachers, classmates, and community members have shared stories of the boy who made every room brighter. One teacher wrote, “Jaysen had a spark — that rare kind of kindness that made people feel seen. His absence is felt everywhere.”

Through their tears, Clarence and Ebony have found a new purpose. They’ve vowed to dedicate their lives to spreading awareness, to make sure no other child loses their life this way.

“We can’t bring him back,” Clarence said quietly. “But maybe we can save someone else’s child. That’s what Jaysen would’ve wanted.”

Health experts agree that awareness is the only true weapon against this silent killer. Dr. Allison Greene, an infectious disease specialist, explained,

“People don’t realize how rare this infection is, but when it happens, it’s almost always fatal. Education is our strongest defense. People need to know where this amoeba lives and how to prevent exposure.”

She also reminded the public that you cannot get infected by drinking water — only when contaminated water enters the nose, often during activities like diving or jumping into lakes.

Lake Murray remains open, though signs are expected to be placed warning swimmers about potential risks. For the Carr family, those signs are more than warnings — they are reminders of what was lost, and what must never be repeated.

Ebony still replays her last conversation with Jaysen in her mind.

“He told me he loved me before he went swimming,” she said. “He always did. That was just who he was.”

Her husband nodded, eyes full of quiet pain.

“He was full of life. You never think something like this could happen on a normal day. But it did.”

As they try to navigate their new reality, the Carr family plans to honor their son’s memory by creating a nonprofit foundation focused on education and water safety — spreading information to schools, communities, and families across the South.

“We’ll make sure the world knows his name,” Ebony said. “And we’ll make sure no other parent has to live this nightmare.”

For now, they take each day as it comes — finding comfort in memories, in faith, and in the small gestures of kindness from strangers. The world may have lost Jaysen far too soon, but his story, his light, and his legacy will continue to ripple through the hearts of everyone who hears his name.

Rest in peace, Jaysen Carr.

Your life may have been short, but your impact will never fade.