The day Claire died, the house forgot how to breathe. Every corner, every creaking floorboard, every draft that used to feel familiar now carried a quiet accusation. Morning light still poured through the living room windows, turning the motes in the air into drifting gold, warming the cushion of her favorite chair the way it had for decades. But it felt wrong, alien, like sunlight itself didn’t know where to land without her. I stood in the doorway staring at that chair, half-expecting the soft rustle of pages, the slight shift of her legs crossing, the look she’d give me when I hovered instead of committing to a conversation.

“You’ll never win an argument standing in a doorway, James,” she used to say, one eyebrow arched over the rim of whatever book she was devouring. “Come sit down and face the music.”

I heard it so clearly that my chest constricted. She had said it once when I suggested we paint the kitchen beige. She looked at me like I had proposed burning the house down for fun.

“Beige?” she’d repeated, scandalized. “James, darling, we are not beige people.”

We weren’t. Claire brought color into everything—our home, our marriage, our lives. She could turn a grocery run into a story, a bad day into a joke, a quiet afternoon into a memory you carried with you. She was messy and brilliant and stubborn, a person who loved like it was a conscious decision she made daily, not a feeling she waited for. Losing her wasn’t just grief; it was the sudden disappearance of the person who made reality feel livable, who gave ordinary moments warmth and texture, who made our family feel whole.

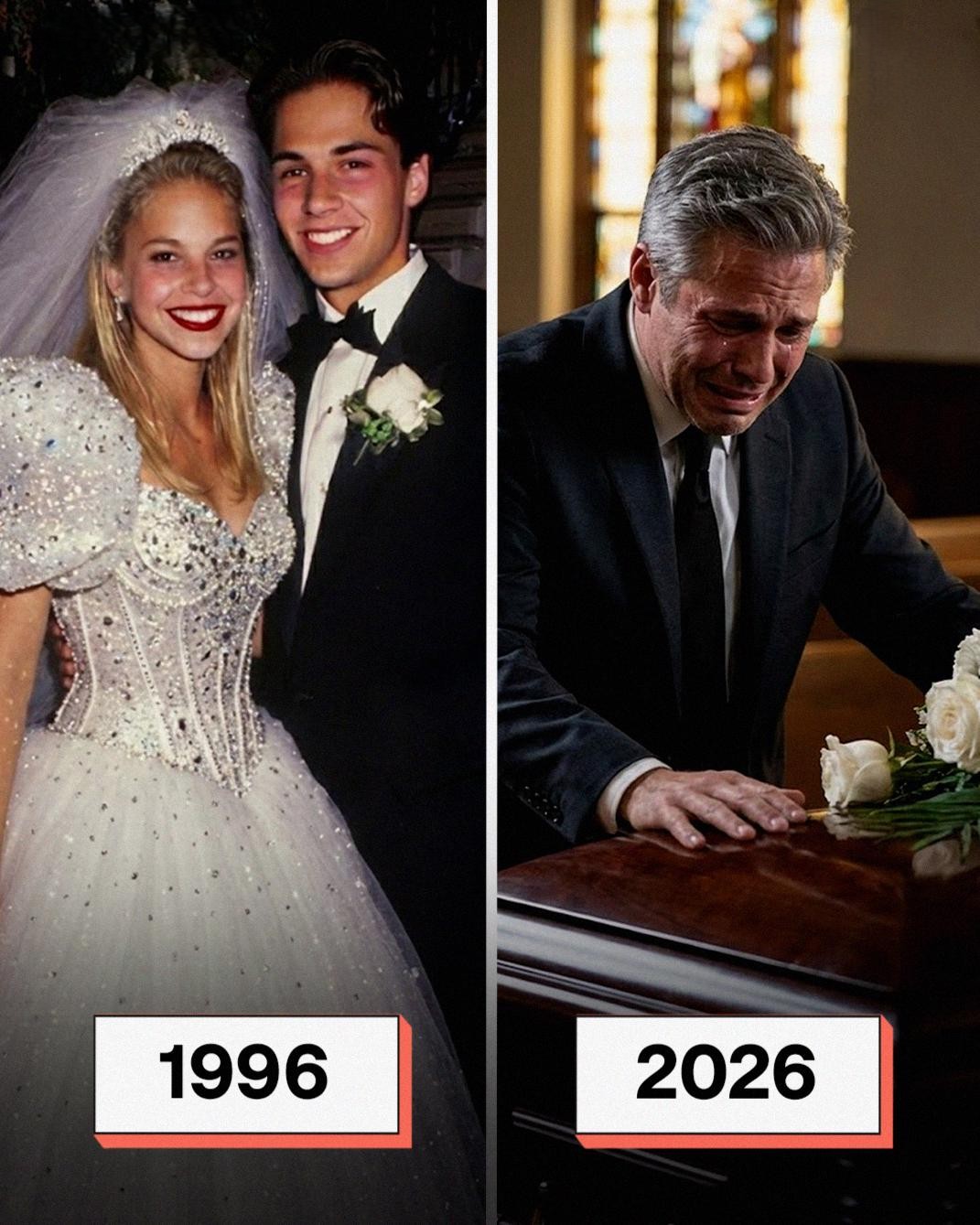

We had raised two kids together, Pete and Sandra. We’d fought about curfews and college choices, argued over whether children needed strict schedules or room to breathe. We’d made up in the quiet hours with tea in bed, apologies that weren’t dramatic but were sincere. We had inside jokes and unspoken rituals, the kind of long marriage you don’t even realize is strong until you look back and see how many storms you walked through without losing each other. Every laugh, every shared glance across a crowded room, every “I’ve got you” in the middle of a disagreement had added to an invisible scaffolding that kept us steady.

Her illness moved fast. Too fast. One moment she was planning a weekend away at a coastal inn, folding her favorite cardigan and insisting she wanted a balcony and “absolutely no emails.” The next, we were sitting in a hospital room listening to machines beep softly like they were trying to speak a language we couldn’t understand, a language of inevitability and sorrow. On her last night, Claire reached for my hand like it took effort and held it with the gentlest certainty.

“You don’t have to say anything,” she whispered. “I already know.”

I nodded because if I spoke, my voice would have cracked into pieces. I wanted to freeze time, to bargain with anything that might listen. But all I could do was hold her hand and keep breathing, like that could somehow keep her here.

After the funeral, I drifted through the house like a ghost. Her chamomile tea sat cold on the nightstand. Her glasses were folded beside the book she’d been reading. Her sweater still hung over the back of the chair, as if she’d simply stepped away for a moment. I couldn’t bring myself to move anything. Touching her things felt like admitting she wouldn’t come back, like accepting a truth I wasn’t ready to face. Every room seemed to echo with her absence. The living room smelled faintly of vanilla and old books, the kitchen carried the aroma of morning coffee that would never be hers again, and even the garden, meticulously tended, seemed to droop as if mourning.

Three days later, I went looking for her will. Practical tasks have a way of forcing you into motion when grief tries to turn you into stone. That’s when I found the box. It was in the back of our bedroom closet, shoved beneath winter coats and old photo albums. The tape sealing it looked new, as if Claire had packed it not long ago. My hands shook as I carried it to the bed. I expected old letters, keepsakes, maybe a card she’d saved because she liked the handwriting. Something small. Something familiar.

Instead, I opened the lid and saw a manila envelope.

I pulled it out. Opened it. And my breath stopped.

A divorce decree.

Claire’s name. My name. A judge’s signature. A date stamped across the page: twenty-one years ago.

My brain refused it at first, like it was a mistake, like the document belonged to someone else. But the signatures were there. Claire’s graceful handwriting. Mine, tight and uneven, like I’d signed while shaking. I stared until my eyes burned. I didn’t remember this. I didn’t remember filing for divorce. I didn’t remember agreeing to it. But then a hazy memory pressed in from somewhere deep and broken: the accident. Route 5, sleet slicking the road, the violent spin, the sound of metal, then nothing. Weeks in the hospital. Surgeries. A coma. When I finally woke, pieces of my life were missing. The doctors warned me memory loss was common. Claire had filled in what I asked about, but she never forced the missing chapters back into me. And maybe I hadn’t asked enough. Maybe I trusted the life in front of me because it felt true.

We had celebrated anniversaries. We had worn rings. We had toasted and laughed and planned futures. Last year, for what I thought was our thirtieth anniversary, I gave her a necklace with a swan pendant. She gave me a fountain pen engraved with my name. We drank wine and she leaned in close and said, “We didn’t run, my love. Even when we wanted to.”

I had taken that as proof of endurance. Now it sounded like something else. Like a confession tucked inside romance.

My hands moved on their own, digging deeper into the box. Another envelope. Another document. A birth certificate.

Lila T. Female. Born May 7, 1990. Mother: Claire T. Father: Unlisted.

Claire had a child. A daughter. Born three years before we got married. A daughter I had never heard of, never met, never even suspected existed. My stomach turned cold. The room felt too small. The air felt thin. Grief was already drowning me, and now it had teeth.

I sat there with papers spread across my bed like evidence at a trial, trying to piece together a life I thought I understood. Had I asked for the divorce while I was recovering? Had I wanted to set her free because I knew I wasn’t whole? Or had she filed because she couldn’t survive the weight of it all? I couldn’t remember. That was the cruelest part. The truth existed, but my mind had holes where the answers should have been.

Then there was a knock at the door. Not the gentle knock of a neighbor dropping off food. This knock had purpose.

I opened the door to a man in a charcoal suit holding an envelope.

“James?” he asked.

“Yes.”

“I’m Mr. Johnson. Your wife’s attorney. May I come in?”

He sat in the living room and handed me the envelope. Claire’s handwriting was on the front: my first name, written the way she labeled spice jars and grocery lists.

I opened it like it might explode.

Her letter didn’t soften anything. It went straight for the truth. She wrote that Lila was her daughter, that she’d been twenty and terrified and had placed the baby with a family she believed could give her stability. She wrote that she never stopped thinking about her, not once. Years later, she had found her again—quietly, cautiously—just before my accident.

Then came the part that made my throat close.

She had filed for divorce while I was still recovering. She wrote that we were fractured, distant, overwhelmed by everything we couldn’t say out loud. She regretted it almost immediately, but when I came home and we fell back into rhythm, she couldn’t bear to tear the life back apart. I wore my ring. She wore hers. I forgot about the divorce. And she let the days keep moving, building a life on top of a paper truth she didn’t know how to resurrect without destroying us.

“I know you feel betrayed,” she wrote. “But please know this: the love we shared was never a lie. Not one moment of it.”

She asked me to reach out to Lila after she was gone. Not to claim her, not to fix her, but to offer her something she had lacked: a person who stayed.