In the quiet, windswept hills of Finistère, Brittany, a story was unfolding — one shaped by loss, perseverance, and an unexpected encounter with nature’s fiercest invader.

For Denis Jaffré, a former sailor turned beekeeper, life had found a new rhythm among the hum of bees and the scent of wildflowers. But peace didn’t last. In 2017, his hives — the heart of his livelihood — came under siege from an enemy he couldn’t ignore: the Asian hornet.

These hornets, invasive predators that decimate bee colonies across Europe, had destroyed half of Denis’s hives in just months. Fifty colonies — gone. The loss wasn’t just financial. For Denis, it was personal. “You care for them, you watch them build, and then overnight, everything is wiped out,” he said in an interview.

But instead of giving up, Denis did what problem-solvers do best — he got curious.

He began experimenting in his garage, using scraps of wood, old jars, and nets, determined to design a trap that could stop these hornets without harming other insects. Every prototype failed. He tried changing the size, the scent, the material — until finally, one idea stuck.

It was simple, elegant, and devastatingly effective.

The trap consisted of two parts: a bait container to attract hornets with a natural scent, and a fabric-covered chamber fitted with narrow entry cones — wide enough for the hornets, but too tight for bees and butterflies. Once inside, the hornets couldn’t escape. Other pollinators, however, stayed safe.

It was precise. It was sustainable. And it worked.

By 2019, Denis’s invention caught the attention of experts. His trap won a medal at the prestigious Lépine Competition, France’s oldest innovation fair — a recognition that transformed a local beekeeper’s experiment into a breakthrough for environmental protection.

With that success came a new mission: to make the device available to beekeepers everywhere.

In 2021, Denis founded Jabeprode, a company rooted in his philosophy of ecological responsibility and local craftsmanship. What began as a one-man operation in his living room evolved into a thriving workshop in Bodilis, a small town in northern Brittany. The 480-square-meter facility now houses a small but dedicated team of seven employees who hand-assemble the traps with care and precision.

“We’re not just making a product,” Denis explained. “We’re protecting life.”

The results have been remarkable. Within a few years, Jabeprode’s traps spread across 18 European countries — including France, Belgium, Spain, Italy, and Germany — with growing interest from the United States, where the Asian hornet has recently begun to appear. The design has been praised for its balance of efficiency and ethics: it neutralizes a deadly invasive species without threatening the fragile biodiversity that sustains agriculture and ecosystems.

Denis’s invention didn’t just protect bees; it restored balance.

And that’s exactly what drives him. As a former sailor, Denis has always felt a deep connection to nature’s rhythms — the sea, the seasons, and now, the hum of his hives. He understands that innovation means nothing if it disrupts the natural order. “We can’t fight one problem by creating another,” he often says. His trap is proof that environmental protection and human ingenuity can coexist.

But Denis’s mission doesn’t stop at production. He’s now working to expand education around sustainable hornet control. Too often, panicked homeowners and local councils resort to toxic chemicals or dangerous methods to destroy nests. Denis advocates for more responsible solutions — including controlled use of sulfur dioxide for nest neutralization, which, he argues, is safer for the environment than widespread chemical spraying.

He’s also launched a crowdfunding campaign to purchase and expand his workshop, allowing him to scale up production and meet the growing global demand. The funds would also help finance research into improving the traps and developing new ecological tools for pollinator protection.

Behind the modest exterior of his operation lies a bigger idea: to redefine how we respond to ecological crises. Denis believes in empowering individuals — from small farmers to amateur gardeners — to take part in protecting biodiversity. “Every person can help,” he insists. “Every trap placed in a garden or near a hive makes a difference.”

His dedication has resonated deeply with environmentalists and agricultural groups alike. Beekeeping associations across Europe now credit Denis’s trap with saving thousands of colonies and preventing local honey shortages. His work has also attracted academic attention; researchers are studying his design to better understand behavioral patterns of the Asian hornet and to develop further non-lethal, species-specific traps.

Still, Denis remains grounded. To him, this isn’t about fame or money — it’s about giving back to the creatures that once gave him peace. “Bees teach patience,” he says. “They show you that survival depends on working together. I guess I just tried to follow their example.”

The quiet innovation born in his attic now protects thousands of hives. From his workshop in Bodilis, shipments of his hornet traps head out across Europe every week — small boxes packed with big hope. The once-desperate beekeeper has become an unlikely figure of inspiration, demonstrating how compassion and creativity can transform a personal loss into a global solution.

For Denis, success isn’t measured in profits but in pollination — in the hum of life returning to orchards and fields that might otherwise fall silent. “Every time I see bees back at work, I feel like I’ve done something that matters,” he said simply.

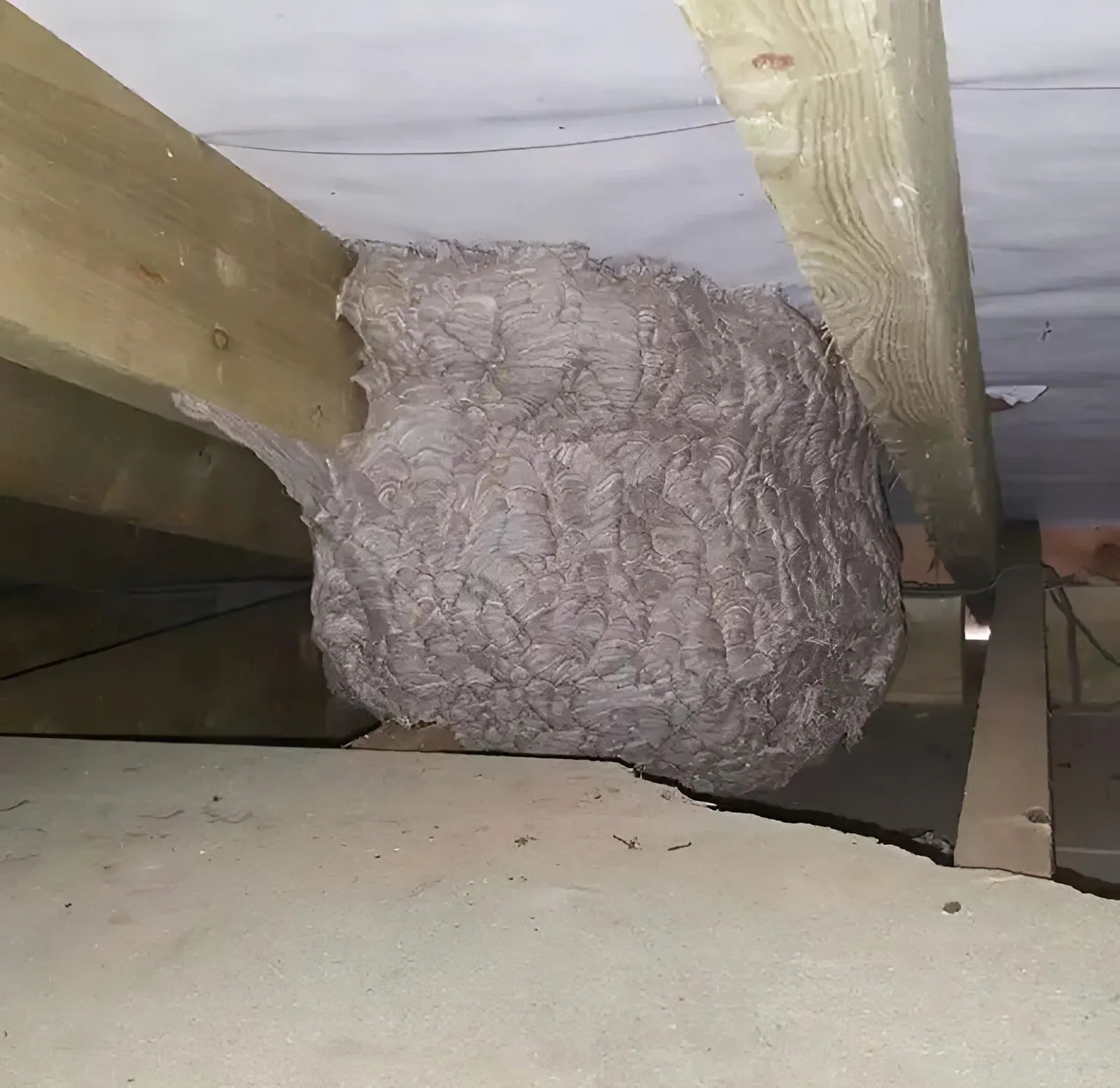

His story stands as a quiet reminder: sometimes, what looks like a problem — even a “hornet’s nest” in your attic — can turn out to be an opportunity. When faced with destruction, Denis chose creation. When faced with loss, he built something that gave life back.

Today, his invention is helping to save bees across continents. But more than that, it’s a testament to one man’s refusal to surrender to despair — and his belief that solutions built with respect for nature are the ones that last.

Because in a world filled with noise, it’s the steady buzz of a healthy hive that still holds the sound of hope.