It started with what I thought was a simple, almost thoughtless birthday gift — a DVD copy of Titanic, wrapped neatly in silver paper with a gold bow that I’d picked up on the way home from work. My wife, Emily, had once mentioned offhand that she loved that movie when it first came out. I remembered her saying how it made her cry, how she saw it three times in theaters back in college. So I figured, why not? It would make her smile, maybe give her a reason to slow down and watch something nostalgic for once.

I never imagined that little silver-wrapped package would become a turning point in our marriage — or that a film about a sinking ship would somehow keep our family afloat.

That morning, she unwrapped it at the kitchen table, sunlight spilling through the blinds. Our three-year-old son, Max, was beside her, bouncing with toddler energy, his cereal half-eaten and milk dripping down his chin.

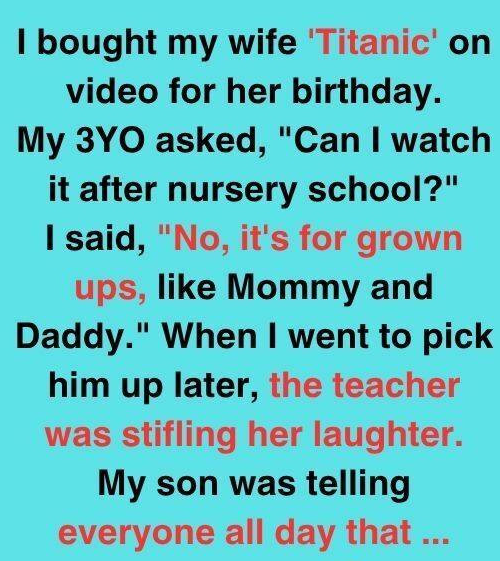

“Can I watch it after nursery?” he asked with that innocent eagerness only little kids can manage.

“Not yet, buddy,” I said, smiling. “It’s for grown-ups.”

He nodded with the kind of seriousness that made Emily laugh. “Okay,” he said. And then that afternoon, he proudly announced to everyone at preschool, “Mommy and Daddy watch Titanic alone at night!”

By pickup time, half the teachers were chuckling. A few parents gave us knowing looks. When they told us what he’d said, we laughed, too. But when the laughter faded, something lingered — not embarrassment, but realization. That single, funny comment captured something uncomfortable and true. Emily and I did mostly do things separately. Dinner together had become rare. Our conversations were quick, logistical, about grocery lists, bills, bedtime routines. Our lives had become two straight lines — close, parallel, but rarely crossing.

Still, that night, after Max fell asleep, we watched Titanic.

It felt strange at first — sitting next to each other, not talking, not distracted by phones or work. Just… watching. The room was dim except for the flicker of the TV. During the opening credits, Emily leaned her head on my shoulder. It was the first time in months that her touch felt easy, natural.

When the ship hit the iceberg, she whispered, “They were going too fast. Ignoring the warnings.”

“Yeah,” I murmured. “They thought they were unsinkable.”

We didn’t talk about it after that. We didn’t need to. The metaphor was obvious — painfully obvious.

The next morning, Max climbed onto my lap, his small hands sticky with jam. “Daddy, why didn’t the captain see the iceberg?” he asked.

I hesitated, searching for words. “Sometimes people go too fast,” I said. “And when you go too fast, you can miss what’s ahead.”

He nodded like he understood. Then, with the brutal honesty only a child can wield, he said, “That’s what happened to you and Mommy.”

The world stopped. Emily froze mid-sip, her coffee halfway to her lips. We looked at each other across the table, and for a moment, I swear, time stood still. Because he was right. Our three-year-old had just voiced what neither of us had dared to say out loud.

We had rushed through everything — through our whirlwind romance, through marriage, through the chaos of parenthood that came earlier than planned. We loved each other, no doubt about that. But we’d built our life like the Titanic: grand, fast, beautiful, but careless with the map. Somewhere between bills, sleepless nights, and long work hours, we’d stopped steering.

And somehow, it took a movie — and a three-year-old — to show us that.

Over the next few weeks, Max’s fascination with the Titanic grew into a full-blown obsession. But it wasn’t dark or sad. It was… curious. Gentle. Thoughtful. He built tiny ships from Duplo blocks, floated them in the bathtub, and even used conditioner caps as lifeboats. Every night, he asked new questions — “Why didn’t they slow down?” “Did everyone help each other?” “What happened to the people who didn’t get boats?”

Emily and I found ourselves answering together, sometimes for hours. We explained teamwork, kindness, mistakes. In teaching him, we started talking again — really talking — not about chores or work, but about feelings, about how people lose sight of each other when they’re busy trying to stay afloat.

We started small. We cooked together again — pasta on Tuesdays, pancakes on Sundays. We took short walks after Max’s bedtime. We didn’t fix everything overnight, but little by little, we remembered what it felt like to be partners. It wasn’t a cinematic reconciliation, no swelling music, no dramatic kiss in the rain. It was quiet. Steady. Like learning to steer again after drifting too long.

Years passed. Max grew taller, smarter, and somehow even more obsessed with ships. When he was nine, we took him to Halifax to visit the Titanic exhibit. I remember watching him walk through the gallery, his small hand tracing the glass cases, his face a mix of wonder and sadness. When he stopped in front of a piece of recovered hull, his voice dropped to a whisper.

“This is where it happened,” he said.

It wasn’t a question. It was reverence.

Later, in the gift shop, he spent his allowance on a small model of the Titanic. That night, sitting by the hotel window overlooking the harbor, he looked up at me and said, “Even the biggest ships need to be humble. Or else they’ll sink.”

He said it like a passing thought, but it hit me harder than anything I’d ever read or heard. Out of the mouths of children, they say. I looked at Emily, and she smiled through tears. “He’s wiser than both of us were at his age,” she whispered.

“Yeah,” I said. “Maybe he saved us without even knowing it.”

The years kept moving, but something in us stayed changed. We learned to slow down — not because life got easier, but because we understood what mattered. We fought sometimes, of course. Bills piled up. The world spun faster than we could keep up. But we navigated differently. Together.

When Max turned eighteen, we threw him a small graduation party in the backyard. There was laughter, music, family. As the sun dipped below the horizon, Emily and I stood on the porch, watching him laugh with friends — tall, confident, alive.

After everyone left, he came up to us with a small, neatly wrapped gift. “This is for you and Mom,” he said.

I recognized it instantly — the same Titanic DVD, worn at the edges, the case a little cracked. Inside, there was a folded note in his handwriting.

It read:

“Thank you for steering me through life — even when you couldn’t see the icebergs. Because sometimes the iceberg isn’t the end. It’s the reminder to steer with your heart.”

I read it twice, my throat tight, then handed it to Emily. She cried before she even finished.

That night, we watched Titanic again — same movie, same couch, but everything was different. When the ship hit the iceberg, she reached for my hand, and I squeezed hers back.

Neither of us said a word. We didn’t need to.

Now, years later, Max is twenty-three. He’s studying marine engineering, of course. His apartment is full of ship models, nautical charts, and photos from his training voyages. He still calls every week — sometimes to talk about design or weather systems — and every call ends the same way:

“Remember,” he says, half-joking, half-serious, “even the biggest ships need to stay humble.”

And every time, I remember that little boy with the Duplo ocean liners and the conditioner-cap lifeboats — the boy who unknowingly helped his parents find their way back to each other.

The Titanic didn’t just sink in our house. It became our compass. It reminded us that sometimes the things that break us can also guide us home — if we just learn to slow down, listen, and steer with love.

Because in the end, every family, every marriage, every dream is a ship on its own ocean. And even when the water gets rough, it’s never too late to find your way back to shore.