It was a crisp autumn morning on the university campus, the kind of day where the air felt electric with anticipation and the leaves crunched underfoot like a carpet of whispered secrets. In a large, sunlit lecture hall, students were settling into their seats, some scribbling notes, others half-asleep, and a few already engaged in hushed debates about the exams that awaited them. Among them, one particularly curious student raised his hand, the glint of mischief in his eyes signaling that he had something unusual in mind.

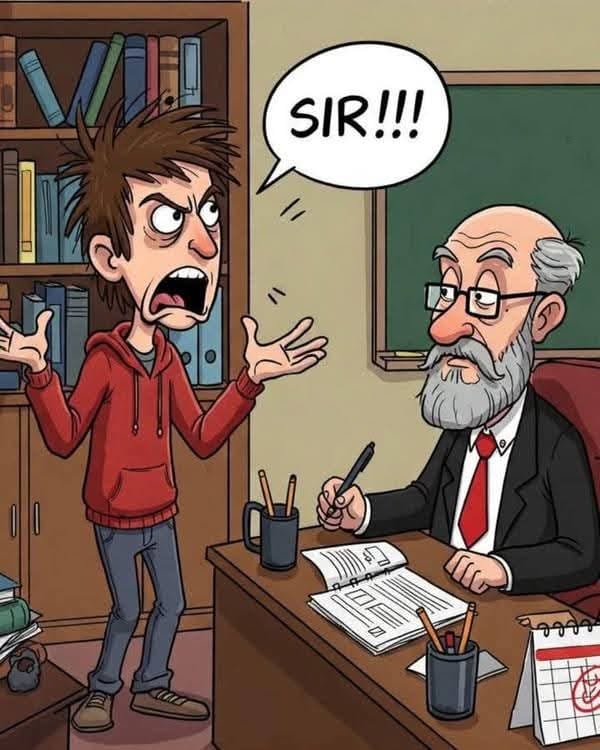

“Sir,” the student began, his voice steady yet tinged with a hint of challenge, “do you really understand anything about the subject?”

The professor, a man of considerable reputation, tall and stern with a shock of white hair that gave him an air of authority, looked over his spectacles. “Surely I must,” he said with a confident smile. “Otherwise, I would not be a professor!”

The student leaned back slightly, a smirk forming. “Great. Well then, I would like to ask you a question. If you can give me the correct answer, I will accept my mark as is and leave quietly. But,” he added, raising a finger for emphasis, “if you do not know the answer, I want you to give me an ‘A’ for the exam.”

The lecture hall went silent. The other students exchanged curious glances, sensing that something extraordinary was about to unfold. The professor, after a brief pause, adjusted his glasses and nodded. “Okay, it’s a deal. So what is the question?”

The student’s eyes gleamed with challenge. “What is legal, but not logical; logical, but not legal; and neither logical nor legal?”

A hush fell over the room. The professor leaned back, furrowed his brow, and began pacing slowly in front of the chalkboard, muttering to himself. Hours seemed to pass in mere minutes as he scratched calculations, wrote possibilities, erased them, and tried again. Sweat began to form at his temples as he realized the riddle was more devious than he had anticipated. No matter how much he thought, no answer seemed satisfactory. Finally, in a moment of exasperation, he sighed and said, “Fine. As agreed, you get an ‘A’.”

The class erupted in whispers, half in admiration for the student’s audacity, half in astonishment at the professor’s concession. But the story did not end there. Later that day, the professor called in his top student, a young man renowned for his razor-sharp intellect and perceptive mind.

He asked him the same question. Without hesitation, the student responded with precision and wit:

“Sir,” he said, “you are 63 years old and married to a 35-year-old woman, which is legal, but not logical. Your wife has a 25-year-old lover, which is logical, but not legal. The fact that you have given your wife’s lover an ‘A,’ although he really should have failed, is neither legal nor logical.”

The lecture hall burst into laughter, and even the professor could not help but chuckle, acknowledging the brilliance and audacity of his best student.

Later, in a linguistics classroom filled with eager students clutching notebooks and coffee cups, the professor began a lesson with his characteristic flair.

“In English,” he declared, “a double negative forms a positive. In some languages, such as Russian, however, a double negative remains a negative. But here’s the key: there is no language wherein a double positive can form a negative.”

From the back of the room, a voice rang out sarcastically, “Yeah, right.” The class erupted, some students giggling, others rolling their eyes, and the professor could only smile at the perfectly timed interruption, realizing that humor was, after all, a universal language.

And then, there was the day of the Psychology professor, a seasoned educator who loved starting his classes with thought-provoking exercises. On the first day of the semester, he stood before a sea of expectant faces and posed a simple yet revealing question.

“Would everyone who thinks he or she is stupid please stand up?”

For a long moment, the room remained silent. The students shifted uncomfortably, glancing at one another as if seeking confirmation that nobody else would dare admit it. Finally, a young man, tall and nervous, hesitantly rose to his feet.

The professor leaned forward, raising an eyebrow. “Well, good morning. So, you actually think you’re a moron?”

The student shook his head, a small grin forming. “No, sir,” he said politely, “I just didn’t want to see you standing there all by yourself.”

The room exploded in laughter, the tension breaking instantly. The professor laughed along with them, recognizing that sometimes the cleverest minds and the sharpest wits were those that could navigate humor as skillfully as knowledge.

From these stories, it became clear to anyone paying attention: intelligence, logic, and humor often intertwine in the most unexpected ways. Whether it was challenging a professor with a seemingly impossible riddle, dissecting the peculiarities of language, or using wit to disarm a tense situation, the lessons extended far beyond textbooks and exams. They were lessons about observation, courage, timing, and the subtle art of thinking — and laughing — in ways others might not expect.

And in the end, perhaps that was the greatest education of all.