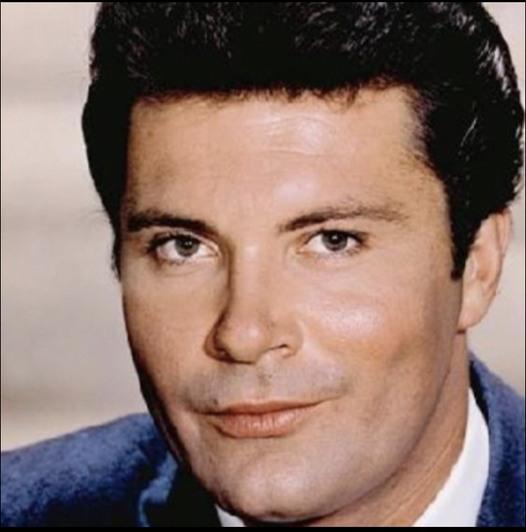

Fame made him a legend, but Hollywood slowly made him disappear. Max Baer Jr. was once one of the most recognizable faces on American television, a performer whose presence felt inseparable from comfort, routine, and laughter. To millions of viewers, he wasn’t just an actor—he was Jethro Bodine, the lovable, dim-witted giant whose wide grin and simple loyalty lit up living rooms week after week. The success was enormous, instant, and overwhelming. But when the cameras finally stopped rolling, the applause faded faster than anyone expected. Acting offers dried up, opportunities vanished, and the laughter that once defined his career gave way to lawsuits, personal loss, and a series of business dreams that never quite reached the finish line. What Baer endured after fame proved far more complex than the role that made him famous.

Being typecast as Jethro Bodine became both his blessing and his cage. The character was so popular, so deeply embedded in American pop culture, that producers could no longer separate the performance from the person. When The Beverly Hillbillies ended in 1971, Baer hoped to evolve—to be seen as a serious actor, a creative thinker, or even a businessman. Instead, casting directors saw only the hillbilly. They overlooked the fact that Baer was intelligent, disciplined, and educated, with a business degree, sharp instincts, and a strong desire to prove he was capable of far more than playing a punchline. Every audition became a reminder that the role that had opened every door was now quietly locking them shut.

Rather than surrender to frustration, Baer pivoted. If Hollywood wouldn’t let him move forward on screen, he would work behind the camera instead. This decision marked a turning point in his life. Stepping into producing and directing, he found a kind of creative freedom that acting had denied him. His most notable success came with low-budget films like Macon County Line, a gritty project made on a shoestring budget that went on to earn millions. The film didn’t just succeed financially—it proved that Baer understood audiences, risk, and storytelling. Quietly and without much fanfare, he became one of the most successful independent filmmakers of his era, even if the public never fully connected that success to the smiling “fool” they remembered from television.

But Baer’s life was never defined by show business alone. Long before fame, he lived in the shadow of his father, heavyweight boxing champion Max Baer Sr., whose career and tragic legacy left a deep emotional mark. The pressure of that history followed him, shaping his sense of responsibility, loss, and identity. Outside of entertainment, Baer found solace in golf, a pursuit that offered structure, discipline, and calm—things often missing from his professional life. Yet even with success and hobbies, personal tragedy touched him deeply. The loss of his girlfriend to suicide left a wound that never fully healed, adding layers of grief that stood in stark contrast to the carefree image audiences associated with him.

Baer continued to dream big. One of his most ambitious plans was to transform The Beverly Hillbillies brand into a chain of casinos and resorts, blending nostalgia, entertainment, and business into something entirely his own. It was a bold idea, and one that reflected his refusal to live only in the past. However, the project became mired in lawsuits, licensing battles, and endless red tape. Despite years of effort, the vision never fully materialized. Still, the dream itself mattered. It showed that Baer never stopped trying to take control of his narrative, to turn what he had been given into something that truly belonged to him.

Now in his eighties, Max Baer Jr. lives largely outside the spotlight. He is the last surviving cast member of the Clampett family, a living link to a television era that shaped American culture. His legacy exists in endless reruns, in familiar theme songs, and in the memories of viewers who still laugh at Jethro’s innocence and loyalty. But behind that gentle, goofy persona was a man far more complex than the character he played—a survivor of typecasting, loss, and disappointment, who fought for decades to be seen as more. In the end, the greatest irony of his career remains clear: the “dummy” America loved was never really dumb at all.