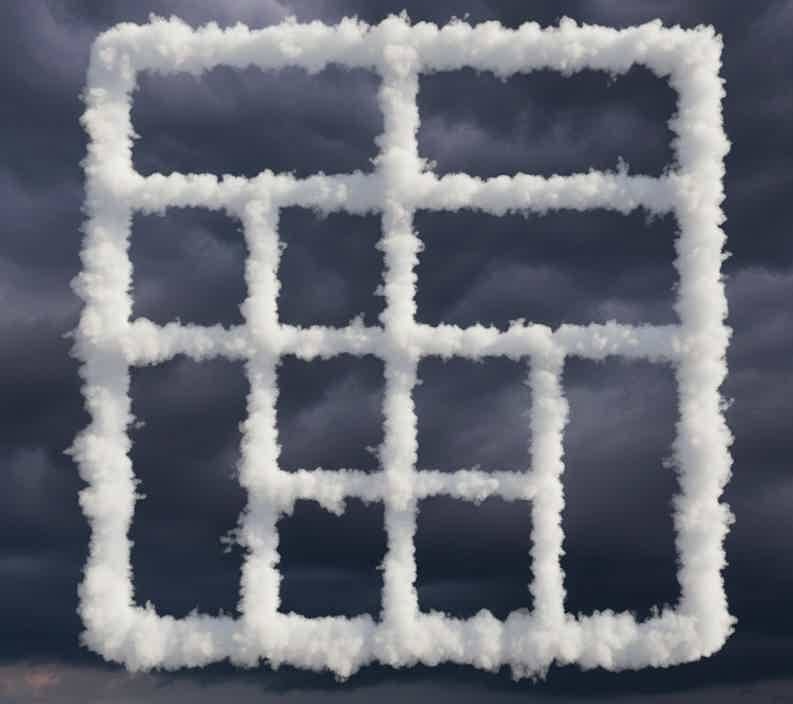

A single cloud of squares. One loaded question. And a ruthless claim: “Most people are narcissists.” At first glance, it’s just a grid—simple, unassuming, almost trivial. Yet the moment you stare at it, something subtle begins to happen. Your eyes scan the arrangement, your mind calculates, and an unexpected tension arises. You count the squares, your fingers hover over the keyboard or the paper, and your brain nags: Did I miss one? Am I supposed to see more? Are others noticing details I’m overlooking? What seems like a casual visual puzzle quietly begins to probe something far more profound. It becomes less about the squares themselves and more about how you process them, how you attend to detail, and how your assumptions shape your perception.

Initially, you start with what is easiest, the low-hanging fruit—the smallest, clearest, most obvious shapes. They practically announce themselves to your attention. It’s satisfying to tick them off, to feel the small victories of recognition. But the puzzle does not settle for that. It asks for patience. With a subtle hint or just the passage of time, larger patterns begin to emerge. Suddenly, what you thought was simple and finite blooms into complexity. You notice overlapping shapes, hidden alignments, or an unexpected symmetry. The grid transforms from a static image into a living study of perception, a reminder that our first impressions are rarely complete.

This process mirrors everyday life more than we often admit. How often do we glance at a person, a headline, or a social media post and think we “know” the story? How often do we form judgments before we’ve looked closely, before we’ve allowed for nuance? The puzzle’s genius lies in how quietly it reveals this habit. It’s not yelling at us; it’s not forcing an answer. It merely reflects back our tendencies to settle too quickly, to prioritize what is visible over what is hidden, to assume mastery over something we’ve only just begun to understand.

And then there’s the subtle emotional layer—the discomfort, the tension, the creeping self-doubt. The claim that “most people are narcissists” adds a psychological twist. It is provocative, yes, but it also acts as a mirror. Are you counting carefully because you are genuinely curious, or because you want to prove something to yourself? Do you hesitate because of uncertainty, or because you fear judgment? The puzzle, simple as it seems, suddenly becomes a meditation on ego, patience, and the human need for certainty.

When you finally notice the larger patterns, the shift is remarkable. It’s no longer about counting squares—it’s about noticing how you count, how you approach problems, how your attention operates under subtle pressure. You realize that what felt like a mundane exercise was actually a lesson in self-awareness, in humility, in the art of perception. The puzzle invites reflection: How many other things in life do we “complete” before they are actually complete? How often do we stop too early, satisfied with the first layer of understanding, oblivious to the richness beneath the surface?

What lingers after you put the puzzle aside is not the correct number of squares, nor the cleverness of the arrangement. It is the uneasy, persistent question: What else am I missing? That question resonates far beyond a single grid. In daily life, it encourages a second look, a slower pace, and a willingness to explore beyond the obvious. It reminds us that life, like the puzzle, often conceals deeper truths that reveal themselves only when we pause, reflect, and approach with patience.

Every detail, every line and corner, becomes a lesson in curiosity. The puzzle teaches that clarity is not a given; it is earned. It nudges us to interrogate assumptions, to challenge our first impressions, and to resist the temptation to settle for easy answers. And perhaps most importantly, it invites kindness toward ourselves and others. By recognizing how prone we are to miss subtlety, we may also become gentler in judgment, more tolerant of uncertainty, and more willing to seek understanding rather than snap conclusions.

In the end, the puzzle is not merely a viral sensation or a clever trick. It is a mirror held up to human perception, an elegant reflection of how we engage with the world. It transforms a simple visual challenge into a meditation on attention, humility, patience, and the rewards of looking closer. And when we carry its lesson into our daily lives, the world begins to feel deeper, more intricate, and infinitely more fascinating.

A single cloud of squares, a question, and a claim may seem trivial—but beneath the surface lies a profound insight: that perception is as much about how we look as it is about what we see. And the beauty of it is that once we notice this, the puzzle never truly ends. Each glance, each reflection, each pause to reconsider becomes a chance to see a little more, understand a little deeper, and appreciate the subtle complexity that exists in both a simple grid and the vast world around us.